Every AI lab now has AGI timelines. Five years, ten years, 2040, 2060. The predictions keep shifting for a reason: we don't have a reliable way to measure whether we're getting closer. Models pass increasingly complex tests while failing at tasks that should be simple if they actually reasoned.

For instance, a model that aces physics tests but fails when problems are rephrased slightly hasn't learned physics. A system that wins math olympiads but struggles with messy PDFs hasn't achieved general intelligence.

This gap (between impressive benchmarks and brittle real-world performance) reveals how far we are from AGI. The timelines keep shifting. The definitions keep changing. The benchmarks keep multiplying. And somewhere in all the noise, the actual technical reality gets lost.

The path to AGI is longer, messier, and more measurement-constrained than the hype cycle suggests. Not because companies lack compute or algorithms, but because the industry fundamentally struggles to evaluate whether we're making real progress or just getting better at gaming synthetic tests.

Let me walk you through what AGI actually means, why current systems fall short in ways that matter more than capability benchmarks show, and what this means for the people doing the work that shapes these systems.

What is artificial general intelligence (AGI)?

Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) is a hypothetical AI system that matches or exceeds human-level performance across virtually any cognitive task. It encompasses the full range of reasoning, learning, and adaptation that humans demonstrate across completely different contexts, not just narrow domains like playing chess or generating code.

Here, the critical word is "general."

An AGI wouldn't just be superhuman at protein folding and mediocre at everything else. It would understand physics equations, write legal briefs, diagnose rare diseases, compose music, navigate complex social dynamics, and learn entirely new domains with the kind of transfer capability humans take for granted.

We're not close to this. Not remotely. But the gap isn't always where people think it is.

What are the differences between AI, ANI, AGI and ASI?

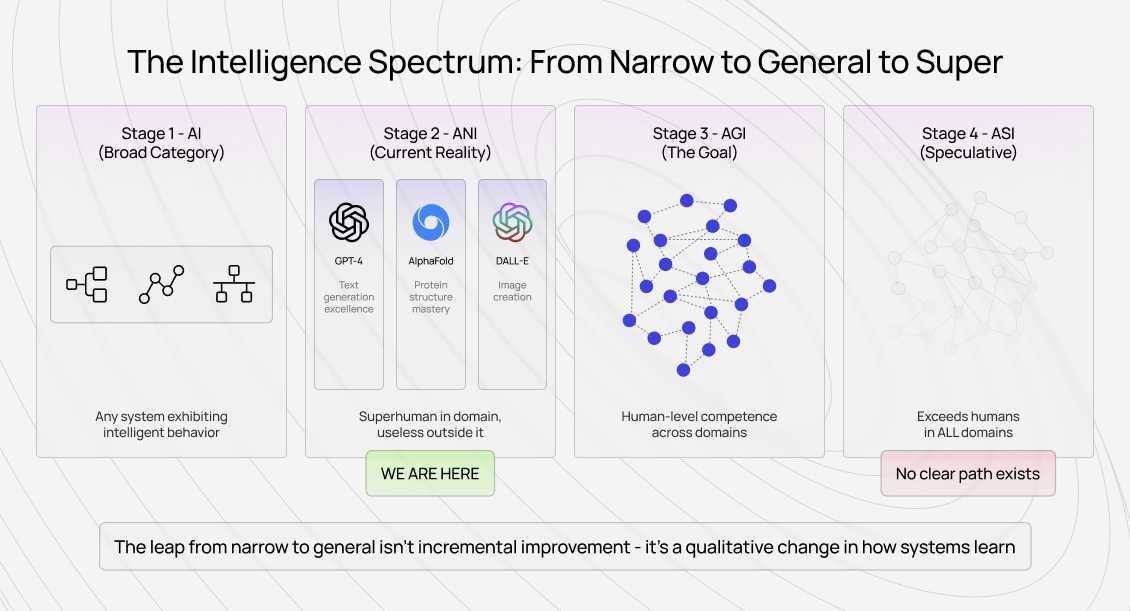

The terminology matters because the distinctions reveal what's actually hard about building toward general intelligence:

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is the umbrella term for any system that exhibits behavior we'd consider intelligent if performed by humans. This includes everything from rule-based expert systems to modern neural networks.

When people say "AI" today, they usually mean machine learning systems trained on large datasets — but the term itself is deliberately broad. It encompasses both the narrow systems we have and the general intelligence we're building toward.

Artificial Narrow Intelligence (ANI) is what we actually have today. These systems excel at specific, well-defined tasks. For example, GPT-4 generates coherent text, AlphaFold predicts protein structures, and DALL-E creates images from descriptions.

Each is superhuman within its domain and often useless outside it. Claude can write brilliant code, but might not reliably parse a messy PDF. That's ANI. Extraordinary capability married to brittle boundaries.

Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) marks the threshold at which a system demonstrates human-level competence across diverse cognitive domains. It doesn't just perform narrow tasks exceptionally well; it also excels at broader tasks.

It transfers learning between contexts, handles ambiguity without explicit training, and adapts to genuinely novel problems using principles rather than pattern matching. The key distinction from ANI isn't raw performance on any single benchmark. Instead, it's flexible, generalized reasoning that works across domains without retraining.

Artificial Superintelligence (ASI) would exceed human capability across all domains. This is the science fiction scenario: systems that don't just match but vastly surpass the best human experts in every field simultaneously.

ASI doesn't exist, and how we'd build or control it remains almost entirely speculative.

Here are the most significant differences at a glance:

The table reveals something important: the gap between ANI and AGI isn't incremental improvement within existing capabilities. It's a qualitative leap in how systems learn, transfer knowledge, and handle genuine novelty.

Current models are getting better at more things, but "better at more things" isn't the same as "general intelligence." It's still narrow intelligence with broader coverage.

What will be the use cases of AGI?

If we actually achieved AGI (systems with human-level general reasoning), the applications would fundamentally differ from scaled-up versions of current narrow AI:

Scientific discovery: Not just analyzing existing research or running simulations, but formulating novel hypotheses across disciplines, designing experiments humans haven't conceived, and connecting insights between fields in ways that require genuine understanding rather than pattern recognition.

Medical diagnosis and treatment: Beyond matching symptoms to known conditions, this would mean understanding rare disease presentations with limited training data, integrating contradictory test results using clinical reasoning, and adapting treatment approaches based on individual patient complexity rather than statistical averages.

Complex system design: True AGI would architect systems (software, mechanical, organizational) by understanding fundamental principles rather than optimizing within predefined parameters. It could design a bridge, evaluate trade-offs between cost and safety that require judgment rather than calculation, and adapt the design when novel constraints emerge mid-project.

Creative problem-solving: Not generating content in existing styles, but solving problems that require genuine creativity: combining approaches from unrelated fields, recognizing when conventional wisdom doesn't apply, and developing entirely new frameworks when existing ones fail. This is the difference between mimicking human creativity and actually possessing it.

Long-horizon planning: Operating across timeframes that require balancing immediate actions against long-term consequences, adapting plans as contexts shift, and maintaining coherent goals through thousands of intermediate steps. Current systems struggle to plan beyond dozens of steps. AGI would need to think in years, not turns.

An AGI could move between quantum physics, evolutionary biology, and materials science with the same fluidity a human researcher brings to their specialty.

The common thread: these use cases require flexible reasoning that transfers between contexts, not just excellence within predefined domains. That's the technical barrier we haven't crossed.

Why are AGI timelines longer?

The industry loves publishing timelines. Five years. Ten years. "By 2027."

What we've learned watching frontier labs work toward this: the timeline debates usually miss the point. The problem isn't that we need one more breakthrough or twice as much compute. It's that we're systematically underestimating how hard the final stretch is.

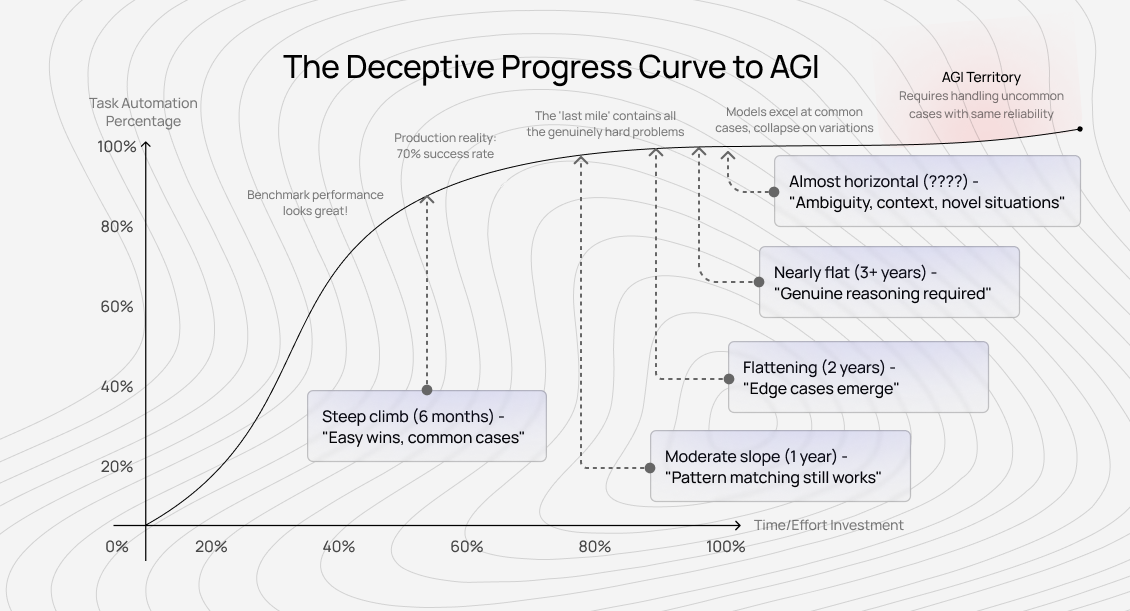

The 80% to 99.9% problem

Here's the pattern we see repeatedly: a lab trains a model that automates 80% of some cognitive task — say, writing code for a software engineer. The next version reaches 90%. Then 95%. And suddenly, progress slows dramatically.

The gap from 80% to 90% might take six months. From 90% to 95%, another year. From 95% to 99%, two more years. From 99% to 99.9%, longer still. This isn't just diminishing returns on investment. It's a qualitative difference in what needs to be solved.

That final 1% often contains all the genuinely complex cases: the edge conditions that require real reasoning, the ambiguous situations where multiple interpretations could be valid, the moments when context from completely different domains suddenly matters. Current systems excel at the common case. AGI requires handling the uncommon case with the same reliability.

A researcher at a frontier lab once told me that their team spent 7 months improving their model's performance on a coding benchmark, increasing it from 85% to 92%. Then they deployed it in production.

The real-world success rate? 70%, because the benchmark captured the easy cases and missed all the messy reality that makes coding actually hard. These include unclear requirements, legacy system constraints, and code that needs to integrate with numerous, poorly documented APIs.

The path to AGI isn't a smooth curve. It's a series of plateaus, each requiring fundamentally different solutions than the last.

Models can't transfer learning between domains

I can train a model to be superhuman at writing Python code. Another to excel at medical diagnosis. A third to master legal reasoning. That's three narrow intelligences, not general intelligence.

The hard part isn't achieving high performance within domains — we can often do that with enough quality training data. The hard part is the transfer.

A human software engineer doesn't just write code:

- They understand when a technical solution won't work because of organizational politics

- They recognize that the real problem isn't what the stakeholder asked for

- They know when to cut corners and when precision matters

- They transfer learning from past projects to novel situations that only superficially resemble previous work

Current models can't do this. They can't reliably transfer principles learned in one domain to another. They can't recognize when a problem is actually analogous to something they've seen before, but expressed in a completely different way. They excel at interpolation within their training distribution and fail catastrophically just outside it.

This is why models can win gold medals at the International Mathematical Olympiad but struggle to parse a poorly formatted PDF. The IMO problems are complex, but they're hard in a specific, constrained way that rewards pattern recognition over genuine reasoning.

Parsing the PDF requires understanding context, handling ambiguity, and making judgment calls about what the human actually wanted — all the messy, general intelligence work that benchmarks don't capture.

The messy reality beyond benchmarks

The models that score best on public benchmarks can often be the worst at real-world tasks. Not because they're less capable, but because teams optimized them for the wrong objective.

We see this pattern constantly. A team can spend months improving its ranking on a popular leaderboard. Their numbers go up impressively. Then we run human evaluations on actual use cases (the kinds of tasks their customers care about) and discover that the model has gotten worse.

They've trained it to emit longer responses with more formatting and markdown headers because that's what makes rapid evaluators on the leaderboard prefer one response over another.

But real users don't want maximally long responses. They want responses that actually solve their problem. Real doctors don't want confident-sounding medical explanations full of emojis. They want correct diagnoses supported by reasoning they can verify.

Real engineers don't want code that looks impressive. They want code that works in production with their specific constraints.

This isn't a minor problem. It's a fundamental measurement challenge that scales directly with capability. The more powerful the model, the more ways it can find to game evaluation metrics that don't actually capture what we care about.

And AGI, by definition, requires solving problems where we often don't even know how to specify what "correct" looks like ahead of time.

The industry can’t benchmark general intelligence yet

Traditional benchmarks work when you can define success clearly:

- For sorting algorithms, you measure speed and correctness

- For image classifiers, you count accuracy on held-out test sets

But how do you benchmark "can reason about novel problems across arbitrary domains"?

The current approach tries to cover many domains with separate benchmarks: coding, math, reasoning, common sense, and scientific knowledge. But passing all these benchmarks doesn't prove general intelligence. It proves you can pass benchmarks. The gap between those two things is precisely what makes AGI hard.

We've watched teams discover this the hard way. They'll train a model that achieves impressive scores across different evaluation suites. Then we run it on tasks that feel similar but weren't in the benchmark set (maybe legal reasoning instead of general reasoning, or debugging code instead of writing it from scratch), and performance collapses.

The model learned to excel at the specific task formulations in the benchmarks, not the underlying general capability that the benchmarks were supposed to measure.

The fundamental issue: benchmarks work best for narrow, well-defined tasks. But general intelligence is precisely the capability that doesn't fit narrow definitions.

We're trying to measure something that resists measurement, which makes it nearly impossible to know whether we're actually making progress or just improving our models' performance on tests.

The road to AGI: what building toward it requires

If I've learned anything from working at the center of how these systems get trained, it's that the path to AGI doesn't run primarily through more compute or better algorithms. Those matter, but they're not the bottleneck.

The bottleneck is measurement, evaluation, and the quality of human intelligence we use to shape these systems.

Moving beyond compute and algorithms

The industry narrative focuses on scale: bigger models, more parameters, longer training runs. And yes, scale unlocks capabilities. But it also amplifies whatever's already there — including all the ways models fail to understand what they're doing.

We've watched teams discover this repeatedly. They'll scale up their model 10x. Performance improves on benchmarks. Then they deploy it, and the failure modes are the same, just more confident.

The model still hallucinates facts, just with more elaborate justifications. It still fails on reasoning tasks that require genuine understanding, just with longer explanations for why it's right when it's wrong.

The problem isn't insufficient scale. It's that the industry is scaling the wrong things. We're scaling parameter count without scaling our ability to evaluate whether those parameters are learning genuine capabilities or sophisticated pattern matching.

More compute and better algorithms will continue to improve narrow capabilities.

But the leap to general intelligence requires solving problems we barely understand how to specify:

- How to evaluate reasoning rather than just answers

- How to distinguish genuine understanding from statistical mimicry

- How to measure whether a model can actually transfer learning between domains or just appears to because it saw similar examples in training

We're scaling training data without scaling the quality of that data or the measurement systems that determine what "quality" means.

Human intelligence remains a bottleneck

Every major capability breakthrough in the last few years came from better human data, not just more data or bigger models. The leap from GPT-3 to ChatGPT wasn't primarily architectural — it was RLHF, which means human feedback shaping model behavior toward what humans actually find helpful.

Claude's excellence in coding didn't come from sheer scale. It came from careful human evaluation of code quality, security, and maintainability — the kinds of judgments that require genuine expertise and can't be automated away.

The models that perform best in production are those trained on data that captures human expertise, not just data volume.

This creates a fundamental constraint on the path to AGI: you can't build general intelligence that surpasses human reasoning without first capturing human reasoning at scale. Not just human outputs (text, code, images), but human judgment about quality, correctness, and usefulness across diverse domains.

The challenge scales directly with capability:

- Training a model to write simple code requires basic correctness checking.

- Training a model to write production-grade code requires expert judgment about security vulnerabilities, performance implications, and maintainability trade-offs.

- Training a model with general coding intelligence would require capturing the kind of reasoning that lets human engineers navigate ambiguous requirements, architectural constraints, and business context.

This is why we believe quality measurement is the actual bottleneck.

The teams that figure out how to systematically capture expert reasoning at scale and measure quality in ways that transfer across domains are the teams that will actually make progress toward AGI.

Expert AI training work at unprecedented scale

If human intelligence is the bottleneck, then the work of capturing that intelligence becomes more valuable, not less, as systems get more capable. This contradicts the automation narrative you usually hear, but it aligns with what we see in practice.

Five years ago, AI training work focused on simple classification tasks:

- Is this image a cat or a dog?

- Does this text express positive or negative sentiment?

The required skills were attention to detail and the ability to follow instructions. Any educated person could do it reasonably well.

Today, the most valuable training work requires domain expertise, critical thinking, and the kind of judgment that takes years to develop:

- We need mathematicians who can evaluate whether a proof is not just correct but elegant.

- We need programmers who can assess code not just for functionality but for security, maintainability, and architectural soundness.

- We need domain experts who can evaluate model outputs on the kinds of edge cases and ambiguous scenarios where genuine expertise matters.

The progression continues. As models handle more of the routine cognitive work, the training work shifts toward the more complex cases — the situations where expertise really matters, where judgment calls are necessary, where there's no single correct answer but some responses are clearly better than others.

This means AI training work is becoming more like traditional expertise work and less like mechanical tasks. The compensation reflects this: rates for expert-level annotation have increased significantly as labs realize that quality at the high end matters more than volume at the low end.

Human evaluation that scales with capability

The career trajectory for skilled annotators increasingly resembles consulting or specialized contract work rather than commodity labor.

The reason this matters specifically for AGI: the closer we get to general intelligence, the more we need human intelligence to evaluate whether we're actually making progress or just gaming narrower metrics.

You can automate evaluation for simple tasks. You cannot automate evaluation for genuine general intelligence, because that requires the very capability we're trying to build.

What is the timeline to AGI?

When people ask me for AGI timelines, I can't give a reliable number — and no one else can either. My answer focuses less on when models will achieve specific capabilities and more on when we'll develop robust ways to measure and evaluate those capabilities.

That's the real bottleneck.

The measurement gap determines everything

We already have models that seem superhuman on narrow benchmarks.

But we don't have reliable ways to determine whether those capabilities reflect genuine understanding or merely sophisticated pattern-matching. We can't consistently evaluate whether a model truly reasons about novel problems or just pattern-matches against similar examples from training.

We struggle to measure whether improvements on synthetic tests actually translate to real-world usefulness.

This measurement gap creates a fundamental uncertainty in any timeline prediction. Maybe we're closer to AGI than benchmarks suggest, because models have more general capabilities than narrow tests reveal.

Or maybe we're further away, because impressive test performance masks brittleness that only shows up in deployment. Without better measurement, we genuinely don't know.

Progress requires solving evaluation first

Progress toward AGI requires solving the measurement problem, not just the capability problem. That means investing in human evaluation infrastructure, developing better ways to capture expert judgment at scale, and building evaluation frameworks that actually test for general intelligence rather than narrow task performance.

It also means the work of training and evaluating AI systems becomes more sophisticated, not less. The path to AGI runs through better ways of measuring whether we're making real progress — and that requires human intelligence that can't easily be automated away.

The wrong question, the right question

The timeline question might be the wrong question.

The better question: are we building evaluation systems that would actually tell us if we achieved AGI, or are we optimizing for metrics that let us fool ourselves about progress? Because if it's the latter, the timeline could be far longer than anyone expects.

Contribute to AGI development at DataAnnotation

If your background includes technical expertise, domain knowledge, or the critical thinking to evaluate complex trade-offs, AI training at DataAnnotation positions you at the frontier of AGI development.

Over 100,000 remote workers have contributed to this infrastructure.

If you want in, getting from interested to earning takes five straightforward steps:

- Visit the DataAnnotation application page and click "Apply"

- Fill out the brief form with your background and availability

- Complete the Starter Assessment, which tests your critical thinking skills

- Check your inbox for the approval decision (typically within a few days)

- Log in to your dashboard, choose your first project, and start earning

No signup fees. We stay selective to maintain quality standards. You can only take the Starter Assessment once, so read the instructions carefully and review before submitting.

Apply to DataAnnotation if you understand why quality beats volume in advancing frontier AI — and you have the expertise to contribute.