You've probably experienced this: you show an AI model like ChatGPT or Claude two examples of what you want, and suddenly it "gets it." The third example comes out perfectly, matching your format, tone, and intent. You didn't train anything. You didn't fine-tune weights. You just showed it what good looks like.

That's in-context learning.

In-context learning has changed how we think about model deployment. And it's created an entire category of work that didn't exist three years ago.

What is in-context learning (ICL)?

In-context learning is the ability of large language models to perform tasks by learning from examples provided in the prompt itself, without any parameter updates or gradient descent. You show the model a few examples of what you want, and it generalizes to new instances; all within a single forward pass.

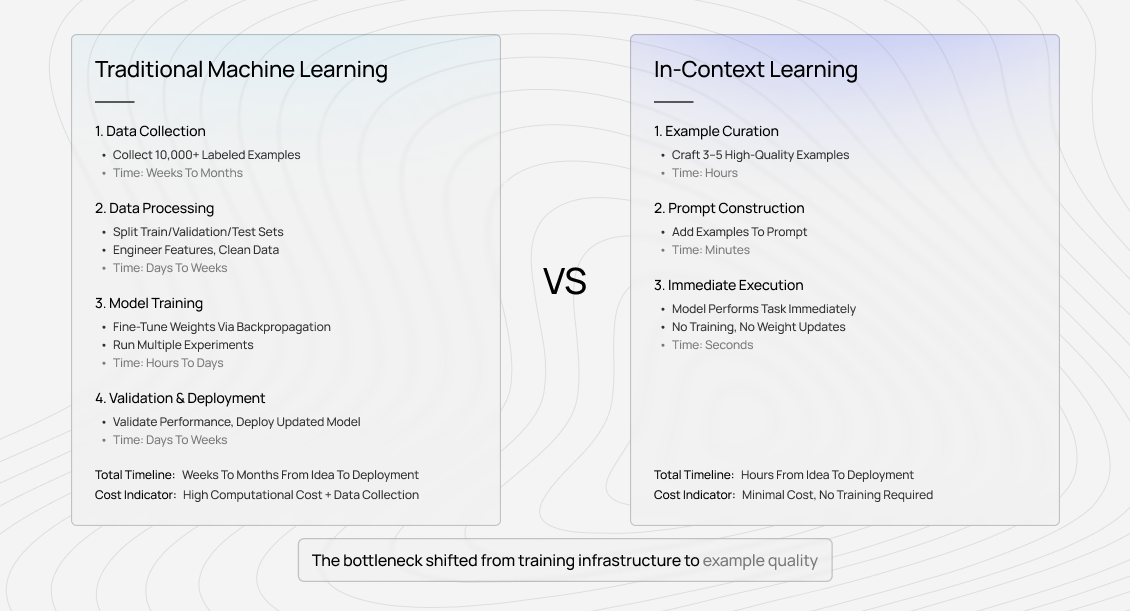

Traditional machine learning requires training: you collect thousands of labeled examples, run backpropagation, update weights, and validate performance. In-context learning skips all of that. The model sees your examples, recognizes the pattern, and applies it immediately.

Here's what that looks like in practice:

The difference isn't just speed. It's that the model's knowledge of language, reasoning, and task patterns (learned during pre-training on trillions of tokens) can be directed toward your specific task solely through examples.

Applications of in-context learning

We see in-context learning deployed across nearly every use case where models interact with domain-specific content:

Classification tasks: Sentiment analysis, content moderation, document categorization, and intent detection. For instance, a legal tech company can show the model three examples of "discovery-relevant" documents, and it generalizes to thousands more.

Information extraction: Named entity recognition, relationship extraction, and structured data parsing. For example, a healthcare system can provide examples of extracting dosage information from clinical notes, and the model handles variations it's never seen.

Generation with constraints: Writing in specific styles, following formatting rules, and matching brand voice. A scenario is where marketing teams show examples of their tone, and the model maintains consistency across hundreds of generated pieces.

Translation and localization: Not just language translation, but domain-specific terminology, cultural adaptation, and technical documentation. A gaming company can provide examples of how they handle in-game text, and the model learns their localization style.

The unifying pattern: you need examples that capture the full complexity of your task, including edge cases and exceptions. Generic examples produce generic results. Domain-specific examples, crafted by people who understand the nuances, deliver reliable performance.

Why in-context learning emerged from scale

In-context learning wasn't designed — it was discovered. When OpenAI scaled up to GPT-3's 175 billion parameters in 2020, researchers noticed something unexpected: the model could perform tasks it wasn't explicitly trained to do, simply by seeing a few examples in the prompt.

GPT-2 (1.5 billion parameters) showed hints of this capability, but inconsistently. GPT-3 made it reliable enough for production use. The capability scaled with model size: larger models could learn more complex tasks from fewer examples, handle more nuanced patterns, and generalize more reliably to new instances.

This wasn't a feature anyone built. It emerged from training on massive amounts of text, where the model learned not just language patterns but meta-patterns — how tasks are structured, how examples demonstrate rules, how instructions relate to outcomes.

The model developed an implicit understanding of "learning from examples" as a general capability rather than a specific, trained behavior.

That emergence changed deployment strategies across the industry.

Instead of fine-tuning dozens of specialized models, companies could use a single large model and steer it through prompts. The bottleneck shifted from training infrastructure to example quality.

How does in-context learning work in AI models?

The mechanism behind in-context learning is still being researched, but we understand the core components from both empirical observation and mechanistic interpretability work.

Attention patterns recognize task structure

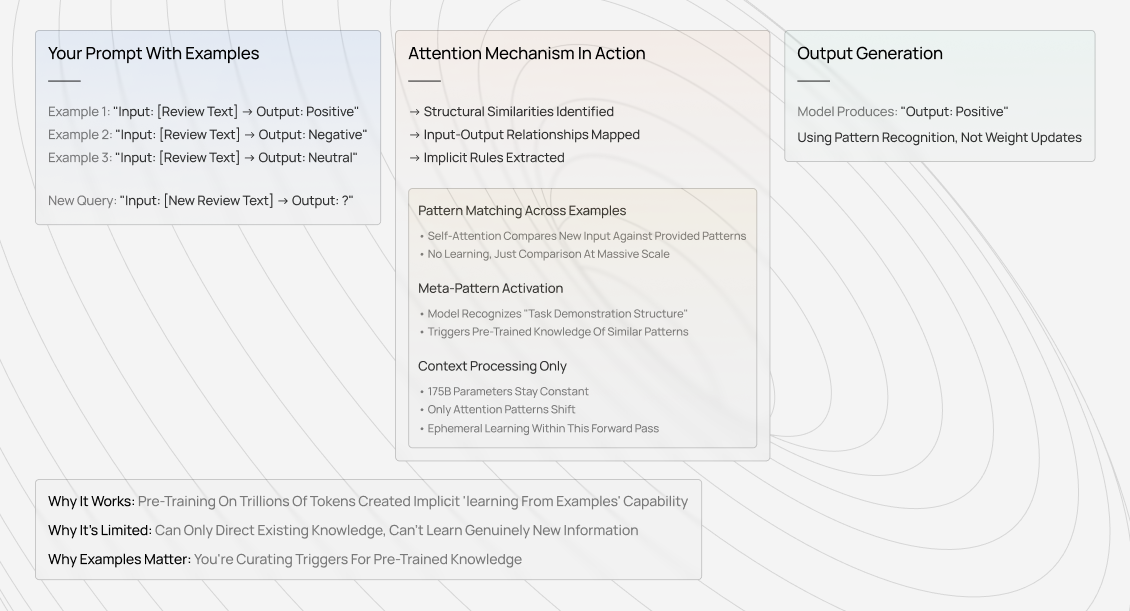

When you provide examples in a prompt, the model's attention layers identify patterns across them: structural similarities, input-output relationships, and implicit rules.

The self-attention mechanism compares your new query against those patterns, effectively performing pattern matching at a massive scale without explicit training.

I've seen this manifest in production: models that perform well on a task immediately after seeing examples can't perform that same task in a new session without those examples. The learning is entirely ephemeral, contained within the forward pass. The model's weights never change; only its processing of the current context.

Pre-training creates meta-learning capabilities

During pre-training on trillions of tokens, models encounter countless examples of "task followed by demonstration" patterns in natural text. Research papers that state a problem and then show solutions, documentation that provides use cases before implementation, and forum posts where someone asks a question, and multiple people demonstrate different approaches.

The model doesn't consciously learn "how to learn from examples." It learns the statistical patterns of what typically follows examples of a particular structure. When you provide examples in a prompt, you're activating those learned patterns. The model recognizes "this looks like a task demonstration structure" and processes your new query accordingly.

Context processing without weight updates

No gradient updates, just context processing. This is what makes in-context learning fundamentally different from traditional learning. The model isn't updating its understanding of the world; it's applying its existing knowledge to the specific context you've provided.

The 175 billion parameters (or 405 billion for Llama 3.1, or 1.8 trillion for GPT-4) stay constant. Only the attention patterns shift in response to your examples.

The practical implication: you can't teach a model genuinely new information through in-context learning. You can only direct its existing knowledge toward specific patterns. If the model hasn't seen concepts similar to your task during pre-training, in-context examples won't bridge that gap.

This is why example selection matters so much; you're not teaching, you're curating triggers for existing knowledge.

Approaches for in-context learning

The field has converged on three main approaches, each with distinct characteristics and use cases. What we've seen in production is that the theoretical boundaries between these approaches matter less than the practical question: how many examples do you need to get reliable performance?

Zero-shot learning

Zero-shot learning is when you provide no examples; just instructions. "Classify the sentiment of this review as positive, negative, or neutral." The model relies entirely on its pre-training knowledge of sentiment, reviews, and classification tasks.

This works remarkably well for common tasks where the model has seen countless similar examples during training. Product reviews, email categorization, and basic summarization are so common in the training data that the model has strong priors.

Where zero-shot breaks: domain-specific terminology, unusual output formats, subtle distinction rules, and edge case handling. I've watched zero-shot prompts achieve 75% accuracy on a classification task, which sounds decent until you realize the remaining 25% contains all the cases that actually matter for the business decision.

The quality ceiling for zero-shot learning is entirely determined by pre-training. If your task pattern existed in the training data at scale, you'll get good results. If it's even slightly novel, you need examples.

Few-shot learning

Few-shot learning is the workhorse of in-context learning; typically, 2-10 examples that demonstrate the task pattern. This is where example quality dominates.

In our work with frontier labs, I've seen the same task perform wildly differently depending on the example selection. A medical coding task went from 68% accuracy with random examples to 89% with expert-curated examples that covered key edge cases. Same model, same prompt structure, different examples.

The key insight: few-shot examples aren't just demonstrations. They're implicit instructions about what matters. If your examples all show clear, unambiguous cases, the model learns "this task has clear patterns." If your examples show edge cases and exceptions, the model learns "this task requires nuanced judgment."

We see this pattern repeatedly when companies bring us prompts that aren't working. The examples are technically correct but pedagogically wrong, as they focus on the easy cases rather than those where the model needs guidance.

Many-shot learning

Many-shot learning emerged as context windows expanded. When you can fit 100,000+ tokens in a prompt, you can provide hundreds of examples. Early experiments showed that some tasks continue to improve with more examples, well beyond the typical few-shot range.

But we've also seen where this breaks down.

One research team provided 500 examples for a classification task and saw a performance plateau around example 50. The additional 450 examples added noise, not signal. The model wasn't learning "more nuance"; it was averaging over redundant information.

The determining factor: task complexity and example diversity. Simple tasks with clear patterns plateau quickly. Complex tasks with meaningful variation continue improving as you add genuinely distinct examples. The challenge is distinguishing between "more examples" and "more useful examples."

From our operational data, many-shot learning is most valuable when you can provide examples that span the full distribution of edge cases, exceptions, and unusual patterns. If your 100 examples are variations on the same theme, you'd be better off with 5 carefully chosen demonstrations of different patterns.

Where in-context learning breaks down

The theoretical elegance of in-context learning ("just show examples and it works") collides with practical reality faster than most teams expect.

Context window limits still bind: Even with 200K token windows, you hit constraints when tasks require both extensive examples and long inputs. Legal document analysis, code review, and scientific literature synthesis — these often require detailed examples and full context. You're forced to choose between example quality and input coverage.

One team we worked with discovered that their contract analysis prompt was truncating examples to fit longer contracts. The model was learning from incomplete demonstrations, producing inconsistent output. They thought they had an in-context learning problem. They actually had an example truncation problem.

Performance inconsistency across similar inputs: This is the pattern that catches teams off guard: in-context learning works brilliantly on test cases, but then fails unpredictably in production. The model handles 90% of cases correctly, but the 10% that fail don't follow obvious patterns.

We've traced this to example coverage. The model generalizes well within the distribution of patterns shown in examples, but struggles with genuinely novel combinations. A customer service classification system worked perfectly for standard requests, but it misclassified anything that combined multiple intent types. The examples showed single-intent cases only.

The example quality bottleneck

Here's what we observe when companies scale in-context learning to production: initial results are promising, performance degrades over time, and investigation reveals example drift.

The task evolves, user inputs change, and edge cases multiply. But the examples in the prompt stay static. What worked in testing stops working in production, not because the model changed, but because the input distribution shifted away from the example distribution.

I've seen this play out dozens of times:

"The model used to handle this fine, what happened?" Nothing happened to the model. The examples stopped representing reality.

The solution is better curation. Teams that treat example maintenance as ongoing work, updating as they encounter new patterns, maintain consistent performance. Teams that treat examples as "set and forget" see gradual degradation.

When models need actual training

In-context learning has a capability ceiling. No matter how good your examples, some tasks require genuine training:

Novel task structures not seen during pre-training: If the pattern doesn't exist in training data, examples can't trigger it. Domain-specific notation, proprietary classification schemes, organization-specific workflows — these often need fine-tuning.

Consistent style or behavior across sessions: In-context learning is ephemeral. If you need the model to maintain the same behavior across thousands of independent queries, fine-tuning embeds that behavior in weights rather than repeatedly providing it in context.

Complex multi-step reasoning chains: When tasks require following intricate procedures with many decision points, in-context examples become unwieldy. Fine-tuning can encode those procedures more efficiently than describing them in every prompt.

The practical test: if you find yourself writing increasingly elaborate prompts with ever-longer example sets, and performance still plateaus, you've hit the in-context ceiling. That's when training becomes necessary.

How in-context learning changed AI training roles

In-context learning created a category of work that didn't exist before: prompt engineering and example curation as specialized labor. But the skill requirements aren't what most people expect.

Writing good prompts is teaching: The researchers and annotators who excel at prompt work aren't necessarily the strongest writers. They're the people who can identify what makes a good teaching example: what patterns matter, what distinctions the model needs to see, what edge cases will trip up generalization.

I've watched expert annotators craft examples that look deceptively simple, only to compare them against randomly selected examples and see a 15-point accuracy difference. The skill is knowing what to highlight, what to contrast, and what to make explicit that would otherwise remain implicit.

Domain expertise matters more than technical knowledge: You don't need to understand attention mechanisms to create effective examples. You need to understand your domain deeply enough to know where the model will struggle.

A medical annotator with clinical experience can identify edge cases a machine learning engineer would miss: "This diagnosis code applies to conditions presenting with specific symptoms, but looks similar to this other code for conditions with a different etiology. The model needs to see examples, distinguishing them."

That's expert curation. That's what in-context learning quality depends on.

The skills that matter for in-context learning work

Pattern recognition across examples: Can you look at 100 instances of a task and identify the 5 that best demonstrate critical distinctions? This is an abstraction skill; seeing through surface variation to underlying structure.

Edge case identification: The bulk of any task is straightforward. Edge cases determine the quality of in-context learning: the inputs where multiple interpretations are valid, where context matters, and where subtle distinctions change the answer.

AI trainers who naturally gravitate toward "wait, what about this case?" thinking excel at example curation. Those edge cases are precisely what the model needs to see.

Quality evaluation for outputs: As in-context learning is deployed more widely, there's an increasing need for people who can evaluate whether the model's output is correct — not just superficially plausible, but actually right according to domain standards.

This is particularly valuable in domains where correctness isn't obvious, such as legal reasoning, medical coding, scientific citation, and technical documentation. The model can generate fluent outputs. Someone needs to verify they're accurate.

Career implications

The work has shifted from "label this data" to "teach this model." The compensation reflects that shift: example curation for complex domains often pays significantly more than traditional annotation because the skill requirements are higher.

But there's a ceiling. In-context learning can't replace training for genuinely novel tasks or consistent behavior across sessions. The work is valuable where examples can effectively teach, in directing existing model capabilities toward specific patterns.

Teams that understand this distinction position themselves correctly: we're not replacing model training; we're enabling deployment without training. That's a narrow but extremely valuable capability, and the people who can do it well are essential to how frontier models get used in production.

The researchers spending three hours on five examples aren't wasting time. They're building the foundation for reliable model deployment. That's skilled labor, and it's compensated accordingly.

Contribute to AGI development at DataAnnotation

In-context learning has transformed how models get deployed, but it hasn't eliminated the need for human expertise; it's concentrated that need into a different form of work. The quality of examples determines whether in-context learning succeeds or fails. The work hasn't disappeared; it's become more specialized and more valuable.

If your background includes technical expertise, domain knowledge, or the critical thinking to evaluate complex trade-offs, AI training at DataAnnotation positions you at the frontier of AGI development.

Over 100,000 remote workers have contributed to this infrastructure.

If you want in, getting from interested to earning takes five straightforward steps:

- Visit the DataAnnotation application page and click "Apply"

- Fill out the brief form with your background and availability

- Complete the Starter Assessment, which tests your critical thinking skills

- Check your inbox for the approval decision (typically within a few days)

- Log in to your dashboard, choose your first project, and start earning

No signup fees. We stay selective to maintain quality standards. You can only take the Starter Assessment once, so read the instructions carefully and review before submitting.

Apply to DataAnnotation if you understand why quality beats volume in advancing frontier AI — and you have the expertise to contribute.