You've probably heard that the Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) solves the fine-tuning cost problem. The pitch sounds familiar: fine-tune your model using 0.01% of the parameters (10,000× reduction), reduce GPU memory requirements by 3× (using ~33% of the original memory), and achieve 90% of the quality. Maybe 95%. Close enough, right?

All true. The method works exactly as advertised.

What they don't mention: cheaper fine-tuning means teams run more experiments on worse data. The efficiency is real. The quality problems just multiply faster.

Production also happens. The model handles straightforward queries perfectly, but stumbles on ambiguous cases, contradictory requests, and anything that requires nuanced understanding beyond that compressed parameter space.

LoRA works exactly as advertised; it makes fine-tuning efficient. What the efficiency narrative misses: the gap between "works on the test set" and "works in production" often widens when you optimize for efficiency over capacity.

Understanding when LoRA enhances your fine-tuning versus when it papers over data problems matters more than understanding the mathematics behind it.

What is Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA)?

LoRA is a parameter-efficient fine-tuning technique that trains small adapter matrices instead of updating all model weights. Rather than modifying billions of parameters during fine-tuning, LoRA freezes the pre-trained model and learns low-rank decomposition matrices that capture task-specific adaptations.

The core insight: most fine-tuning changes happen in a low-dimensional subspace.

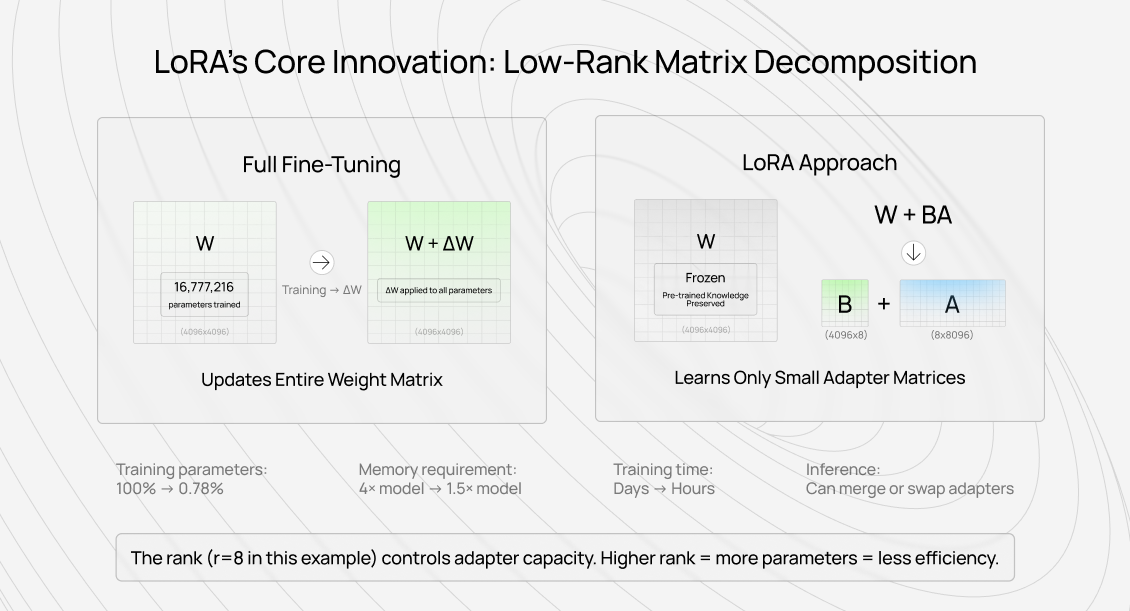

Instead of updating a weight matrix W directly, LoRA represents the update as W + BA, where B and A are much smaller matrices. If W is 1000×1000, you might use rank-8 matrices where B is 1000×8, and A is 8×1000. You're training 16,000 parameters instead of 1 million.

The pre-trained model stays frozen. The adapter matrices learn during fine-tuning. At inference, you can merge the adapters back into the base weights (W + BA becomes a single matrix again) or swap adapters dynamically for different tasks.

Key features of LoRA

Understanding what makes LoRA work helps predict when it won't.

Rank parameter controls capacity: The rank (typically 4-64) determines how many dimensions the adapter uses. Higher rank = more capacity = slower training and larger adapters. The optimal rank depends on task complexity in ways that aren't predictable beforehand.

Layer-specific application: You don't have to apply LoRA to every layer. Common practice: apply only to attention layers (query and value projections); skip feedforward layers. This further reduces the number of parameters but assumes that attention mechanisms require more task-specific adaptation than other components.

Alpha parameter for scaling: LoRA includes a scaling factor (alpha) that controls the extent to which adapter updates affect the base model. Higher alpha = stronger adaptation = more risk of catastrophic forgetting. Teams often set alpha = 2×rank, but this is a convention, not a theory.

Trainable vs frozen components: Everything except the adapter matrices stays frozen. This preserves general capabilities from pre-training while adding task-specific behavior. The assumption: your task is a modification of something the base model already understands, not an entirely new domain.

Merge capability: After training, you can merge B and A back into W, creating a standard model with no inference overhead. Or keep them separate for dynamic swapping. This flexibility is unusual among parameter-efficient methods.

LoRA vs. other AI fine-tuning techniques

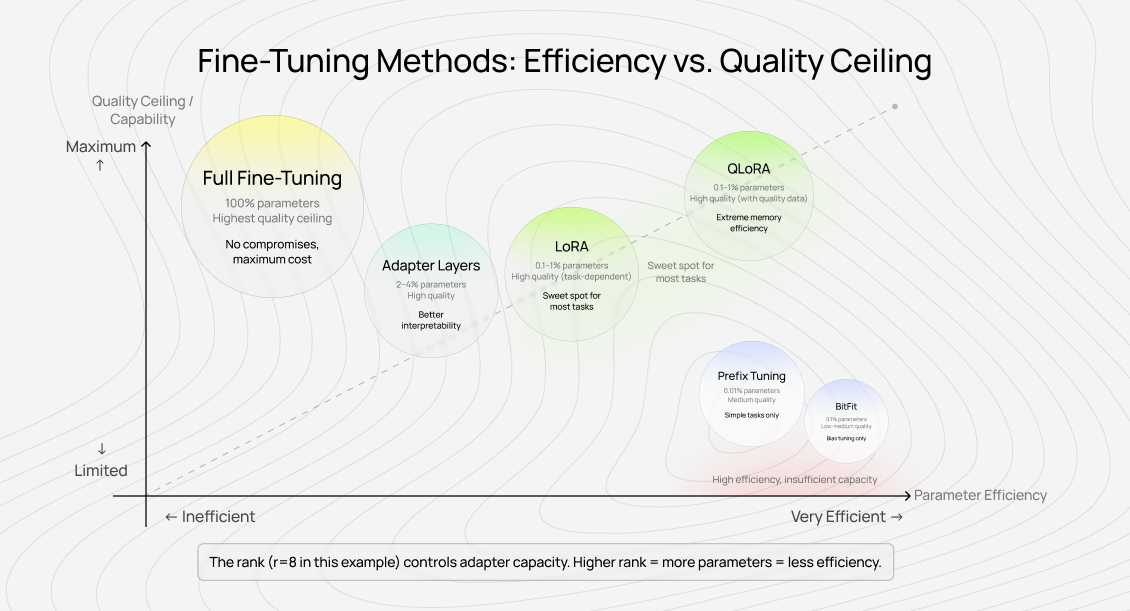

LoRA sits in a crowded space of parameter-efficient fine-tuning methods. Understanding the tradeoffs matters more than following trends.

Each method makes different bets about where model capacity is wasted and where task-specific knowledge lives. LoRA bets that updates happen in low-rank subspaces. Prefix tuning bets that task knowledge fits in prefix tokens. Adapters bet on bottleneck layers. They're all efficient — they're not all effective for every task.

Here are the differences between LoRA and other fine-tuning techniques:

Extreme memory constraints, quantized inference acceptable

The "quality ceiling" column matters most. LoRA typically matches full fine-tuning on narrow tasks (classification, simple instruction-following). It falls short on complex reasoning tasks where the adaptation doesn't fit neatly into low-rank subspaces.

I've run experiments where LoRA and full fine-tuning produced identical validation metrics, but the full fine-tuned model handled edge cases better. The metrics didn't capture what mattered. This is common.

How does LoRA work?

The mathematical foundation is straightforward. The implementation details determine whether it actually works for your use case.

Matrix decomposition approach

Standard fine-tuning updates weight matrix W to W + ΔW, where ΔW has the exact dimensions as W. If W is 4096×4096, you're updating 16 million parameters.

LoRA's insight: ΔW has low "intrinsic rank" — most fine-tuning changes happen in a small subspace. Instead of learning ΔW directly, represent it as ΔW = BA, where B is 4096×r, and A is r×4096. If r=16, you're learning 131,072 parameters instead of 16 million.

During forward pass: output = W×input + BA×input. During training, gradients only flow through B and A. W never changes.

The rank r is a hyperparameter. Low rank (4-8) works for simple adaptations. High rank (64-128) approaches full fine-tuning capacity but loses efficiency benefits.

Attention layer targeting

Most LoRA implementations focus on attention mechanisms — specifically the query (Q) and value (V) projection matrices. The assumption: attention patterns need the most task-specific adaptation.

You can also apply LoRA to key (K) projections, output projections, or feedforward layers, but returns diminish. Attention layers give you most of the adaptation benefit for the cost of the parameters.

This targeting is empirical, not theoretical. Some tasks benefit from LoRA on all linear layers. Others work fine with Q and V only. You won't know until you try.

Scaling and initialization

LoRA matrices use random Gaussian initialization for A (also called Kaiming uniform in some implementations) and zeros for B. This means the adapter starts with zero effect—the model begins training identical to the base model.

The alpha parameter is typically set to match the first rank value tried (the original paper used alpha = r without tuning), though some implementations use alpha = 2r. Higher alpha means stronger adaptation but higher risk of degrading base model capabilities.

I've seen teams chase quality by cranking alpha up, then wonder why the model forgot how to handle basic cases. The base model knew those cases. You just overwrote that knowledge.

Adapter merging

After training, you have options:

Merge into base weights: Compute W_new = W + BA to create a standard model. No inference overhead, but you lose the ability to swap adapters.

Keep separate: Load the base model once, swap different LoRA adapters for different tasks. Adds small inference latency but enables multi-task serving from one base model.

Hybrid approach: Merge your most-used adapter into the base model, keep others separate for exceptional cases.

The choice depends on your production requirements. Most teams merge because simplicity beats flexibility when the flexibility isn't needed.

What are the applications of LoRA in AI development?

LoRA works best when the base model already understands the domain, and you're adapting behavior rather than teaching fundamentally new concepts.

Domain-specific chatbots

You have a general instruction-tuned model. You want it to sound like your company's brand, follow specific response formats, or handle domain terminology correctly.

LoRA works here because the base model knows how to chat — you're tweaking personality and domain knowledge, not teaching conversation from scratch.

A customer support bot for a SaaS product needs to understand the product's specific features and terminology. However, it's still focused on "answer customer questions," which the base model already knows how to do.

We've fine-tuned models for technical support using LoRA with rank 16-32. Training converges in a few hours on consumer GPUs. The model learns company-specific terminology and response patterns without forgetting general conversational ability.

Style and tone adaptation

The base model can write. You want it to write like a specific author, publication, or format.

LoRA captures stylistic patterns efficiently. A technical writing adapter might learn to use active voice, short sentences, and concrete examples. A creative writing adapter might learn to use metaphors, varied sentence structures, and sensory details.

The limitation: style adaptation works when examples clearly demonstrate the pattern. If your style is "high-quality technical writing" but your training examples vary wildly in quality, LoRA learns the average of your data, not the peak.

This is where data quality overtakes method efficiency.

Task-specific instruction following

The base model follows instructions generally. You need it to follow specific instruction formats or domain-specific task patterns.

Example: a code-review bot that must follow a specific review checklist format. The base model understands code and can provide feedback. LoRA teaches it to structure feedback according to your team's conventions.

Another example: content moderation with company-specific policies. The base model generally understands harmful content. LoRA adapts it to your platform's specific policy boundaries and reporting format.

Multi-task serving with adapter swapping

One base model, multiple task-specific adapters. Load different adapters based on user intent or context.

A writing assistant might have adapters for:

- Email composition (professional tone, brevity)

- Technical documentation (clarity, precision, examples)

- Creative writing (narrative voice, description)

- Social media (casual tone, character limits)

Each adapter is 20-50MB. The base model stays constant. You're essentially creating a multitask model without training a single giant model on all tasks simultaneously.

The tradeoff: slight inference latency from adapter swapping, and you need routing logic to select the right adapter. For most applications, the latency is negligible compared to the model's forward pass time.

What the papers don't tell you about LoRA AI training

Research papers report validation metrics, while production use reveals failure modes that metrics miss.

I've watched teams achieve identical loss curves with LoRA and full fine-tuning, then discover that LoRA models fail on distribution edges that full fine-tuning handles. The validation set didn't capture it because validation sets rarely capture what matters in production.

When rank selection fails silently

The LoRA paper suggests rank 4-8 works for most tasks. In practice, task complexity varies more than this suggests.

I've seen rank 8 work perfectly for sentiment classification and fail for multi-turn reasoning tasks on the same base model. Rank 64 helped, but at that point, you're training enough parameters that efficiency gains diminish.

The failure mode is silent. Training loss goes down. Validation metrics look fine. Then you deploy and discover the model handles common cases but fails on anything requiring the kind of nuanced understanding that doesn't fit in a low-rank subspace.

There's no theoretical framework for choosing rank. You run multiple experiments and pick the lowest rank that achieves acceptable quality. This works when you have good evaluation, but "acceptable quality" is harder to define than researchers admit.

The data quality amplification effect

LoRA's efficiency means you can iterate faster. Faster iteration leads teams to focus on method tuning (rank, alpha, layer selection) rather than on data quality. This is backwards.

I've worked with teams that spent weeks optimizing LoRA hyperparameters on mediocre data. They got mediocre results efficiently. When they finally improved their training data quality — better examples, clearer demonstrations of desired behavior, removal of contradictory examples—the model quality jumped even with default LoRA settings.

The efficient method doesn't fix bad data. It makes bad data training faster.

We see this pattern repeatedly: companies generate training data quickly (synthetic data, crowdsourced annotations, scraped examples), then try to compensate with method engineering. LoRA's efficiency enables this mistake at scale.

Catastrophic forgetting in low-rank subspaces

LoRA reduces catastrophic forgetting compared to full fine-tuning, but it doesn't eliminate it. The low-rank constraint protects most base model knowledge, but knowledge that happens to align with the adaptation subspace can still degrade.

Example: fine-tuning for medical Q&A with LoRA rank 16. The model learns medical terminology and reasoning patterns. Six weeks later, users report that the model occasionally gives dangerously wrong answers on basic medical facts that the base model handled correctly.

What happened: the fine-tuning data had a few incorrect examples. Full fine-tuning might have spread these errors across many parameters (diluting their impact). LoRA concentrated the update in the low-rank subspace. When inference queries strongly activated that subspace, the errors dominated.

The fix wasn't changing LoRA settings. The fix was cleaning the training data to remove the incorrect examples.

Why LoRA efficiency doesn't guarantee AI quality

The shift to parameter-efficient fine-tuning coincided with a shift in what people optimize for. Before LoRA, teams fine-tuned carefully because it was expensive. After LoRA, teams fine-tune casually because it's cheap.

Efficiency is now high. Quality variance increased.

The iteration speed trap

LoRA enables fast iteration. Fast iteration feels productive. Teams run experiment after experiment, varying rank, alpha, learning rate, and layer selection.

What doesn't vary: the quality of the training data.

I've reviewed fine-tuning projects where teams ran 50+ LoRA experiments over two months. Different hyperparameter combinations, different random seeds, different layer targeting strategies. Validation metrics varied by 2-3 percentage points. None of the models actually solved the production problem well.

The training data had fundamental issues: examples didn't clearly demonstrate desired behavior, edge cases were missing, and contradictory examples existed. No amount of method tuning fixes this.

The efficient method enabled waste at scale.

Quality measurement lags behind generation speed

You can now generate a fine-tuned model in hours. Properly evaluating whether it works takes longer than training it.

Automated metrics (perplexity, accuracy on held-out test sets) run instantly. They don't measure what matters: does the model handle production edge cases, maintain safety properties, preserve base model capabilities you need?

This requires human evaluation. Comprehensive human evaluation takes days or weeks. The incentive becomes: train fast, evaluate shallowly, iterate to the next experiment.

We see the pattern in customer requests. Teams come to us after months of self-serve fine-tuning with LoRA. They have dozens of model checkpoints. Their automated metrics show steady improvement. Their production results show the models still fail on critical cases.

The diagnosis: they optimized for training speed and validation metrics. They didn't invest in an evaluation that measures actual task quality. The efficient method enabled this mistake.

Method selection distracts from data work

LoRA vs full fine-tuning. LoRA vs QLoRA. Rank 8 vs rank 16. Alpha 16 vs alpha 32. These questions have definite answers through experimentation.

"Is this training example high quality?" doesn't have a definite answer. It requires judgment, domain expertise, and time.

Teams naturally gravitate toward questions with clear answers. Method selection feels tractable. Data quality improvement feels subjective and endless.

But the method's contribution to final model quality is maybe 20%. Data quality is 80%. Spending 80% of effort on method selection and 20% on data quality is backwards.

LoRA's efficiency made method selection even more attractive. You can test five rank values in the time it takes to run one full fine-tuning experiment. This creates an illusion of progress.

The data quality factor in LoRA fine-tuning

Here's what we observe across hundreds of fine-tuning projects: the correlation between method sophistication and model quality is weak. The correlation between training data quality and model quality is strong.

What data quality means in fine-tuning context

Quality isn't about volume or diversity alone. It's about aligning the examples with what you want the model to learn.

High-quality fine-tuning data:

- Demonstrates the exact behavior you want, not adjacent behaviors

- Contains edge cases that matter in production, not just common cases

- Shows consistent quality across examples (no mixing excellent and mediocre demonstrations)

- Excludes contradictory examples that confuse the learning signal

I've seen 500 high-quality examples consistently outperform 10,000 mediocre ones. The smaller dataset had a clearer signal. The model learned faster and generalized better.

The efficient fine-tuning method doesn't change this. LoRA trains on bad data efficiently. Full fine-tuning is expensive on bad data. Neither produces quality.

How annotator expertise shows up in model behavior

We regularly train models on data from expert annotators versus crowdsourced annotators. The difference appears not in validation metrics but in how models handle ambiguity and edge cases.

Example: medical Q&A fine-tuning. Crowdsourced annotators provide technically correct answers. Expert medical professionals provide correct answers that also account for patient context, potential complications, and appropriate hedging.

The model was fine-tuned on expert data:

- Hedges appropriately when certainty is impossible

- Mentions relevant complications the crowdsourced data never referenced

- Uses terminology correctly in context, not just definitionally

Both models achieve similar accuracy on straightforward questions. The expert-trained model handles complex real-world cases better. This doesn't show up in automated evaluation.

LoRA versus full fine-tuning made almost no difference. The quality gap was in the training data, not the method.

Why specialization matters more than you think

General-purpose annotators can follow instructions and format data correctly. Domain specialists understand what good performance actually looks like.

For technical fine-tuning (code, mathematics, scientific reasoning), the specialist understands:

- What makes an explanation genuinely clear versus technically correct but confusing

- Which edge cases matter versus which are contrived

- How real practitioners think about the problem versus textbook approaches

This knowledge doesn't transfer through instruction sheets. It comes from experience.

We've tested this directly: same task, same instructions, general annotators versus domain specialists. The resulting models are measurably different. The specialist-trained models handle real-world complexity better, even though both datasets "follow the instructions."

Method choice (LoRA settings, full fine-tuning, etc.) has minimal impact on this quality gap.

What LoRA advancement means for AI trainers

The efficiency narrative suggests that AI training work becomes less valuable as methods improve. Reality: it becomes more valuable as requirements increase.

Skill differentiation accelerates

When fine-tuning was expensive, most organizations didn't do it. The bar was: can you format data correctly?

Now, fine-tuning is cheap. Everyone does it. The bar is: can you create training data that actually improves model quality?

This separates general data workers from specialists. Formatting skills are table stakes. Domain expertise, quality judgment, and understanding of model behavior become differentiators.

For AI trainers, this means:

- Domain specialization pays more: Generic annotation skills are oversupplied. Deep domain knowledge (medical, legal, technical, scientific) commands premium rates because the work requires genuine expertise.

- Quality evaluation becomes a core skill: Knowing whether a model output is good requires expertise the model doesn't have. This judgment becomes more valuable as models improve at surface correctness.

- Understanding failure modes matters: Recognizing when models fail subtly (technically correct but contextually wrong, precise but misleading) requires experience. This catches problems that automated evaluation misses.

Training data curation over generation

Early AI training focused on data generation: create 10,000 labeled examples. Current work shifts toward data curation: from 100,000 candidates, identify the 1,000 that actually improve the model.

This shift favors different skills:

- Understanding what makes examples valuable versus merely correct

- Recognizing contradictory or confusing examples that degrade training

- Identifying edge cases that matter in production

- Evaluating whether examples demonstrate the desired behavior clearly

These are judgment skills, not production skills. They don't scale the same way data generation scales.

We see this in project structure. Five years ago: "Label these 50,000 images." Now: "From this dataset of 100,000 examples, curate the 5,000 that best demonstrate expert-level performance."

The second task requires expertise. The first required attention to detail.

Career trajectory implications

Efficient fine-tuning methods don't reduce the demand for AI training work. They change what that work involves:

Tier 1 (commodity): Format existing data, follow explicit instructions, and perform basic quality checks. This work compresses toward minimum wage as automation improves.

Tier 2 (skilled): Domain-specific annotation, quality evaluation, edge case identification. This work maintains premium rates because it requires expertise that's not easily automated or crowdsourced.

Tier 3 (specialist): Data curation strategy, training data analysis, model behavior evaluation. This work grows as organizations realize that method efficiency doesn't solve their quality problems.

The path from Tier 1 to Tier 2 is specialization. The path from Tier 2 to Tier 3 is understanding how training data shapes model behavior.

LoRA and similar methods lower the technical barrier to fine-tuning. This doesn't reduce the need for quality training data — it increases competition among organizations trying to fine-tune effectively. Higher competition means higher value on data quality differentiation.

For AI trainers, the question isn't "will efficient methods reduce my work?" The question is "do I have skills that create measurable quality differences in model outputs?"

If yes, demand increases. If not, automation accelerates.

Contribute to AGI development at DataAnnotation

The pattern is consistent across every efficiency breakthrough in AI training: the method speeds up iteration, but quality still depends on the training data. As LoRA and similar methods democratize access to fine-tuning, the competitive advantage shifts entirely to the quality of training data and the human expertise that creates it.

If your background includes technical expertise, domain knowledge, or the critical thinking to evaluate complex trade-offs, AI training at DataAnnotation positions you at the frontier of AGI development.

Over 100,000 remote workers have contributed to this infrastructure.

If you want in, getting from interested to earning takes five straightforward steps:

- Visit the DataAnnotation application page and click "Apply"

- Fill out the brief form with your background and availability

- Complete the Starter Assessment, which tests your critical thinking skills

- Check your inbox for the approval decision (typically within a few days)

- Log in to your dashboard, choose your first project, and start earning

No signup fees. We stay selective to maintain quality standards. You can only take the Starter Assessment once, so read the instructions carefully and review before submitting.

Apply to DataAnnotation if you understand why quality beats volume in advancing frontier AI — and you have the expertise to contribute.