Arrays are the first data structure every developer learns and the last one most truly understand.

The textbook says "elements stored sequentially in memory." What the textbook doesn't say: that sequential layout is why arrays power every performance-critical system in production, and why "theoretically optimal" algorithms regularly lose to "just use an array."

A market data system we analyzed processed 40,000 messages per second using an elegant tree structure. Optimal algorithmic complexity. Clean code. Textbook correctness. The team replaced it with a sorted array that got rebuilt periodically. The "inefficient" approach hit 180,000 messages per second.

The algorithm didn't change. The cache lines did.

This is the first lesson production systems teach about performance: it's physical. Abstract correctness means nothing if it fights the hardware it runs on. The same principle shapes neural network architectures, training pipelines, and arguably biological brains. Efficiency isn't optional overhead, it's a constraint that determines what's actually possible.

What is an array?

An array is a data structure that stores elements of the same type in contiguous memory locations. Access any element by its index in constant time — one multiplication, one addition, done.

int* array = malloc(1000 * sizeof(int));

// Accessing array[500]:

// address = base_address + (index * element_size)

// address = array + (500 * 4 bytes)

// Result: ~0.3 nanoseconds

int value = array[500]; // Direct memory accessEvery word in that definition carries weight that takes years to appreciate:

- Same type means predictable element sizes, enabling that simple address calculation

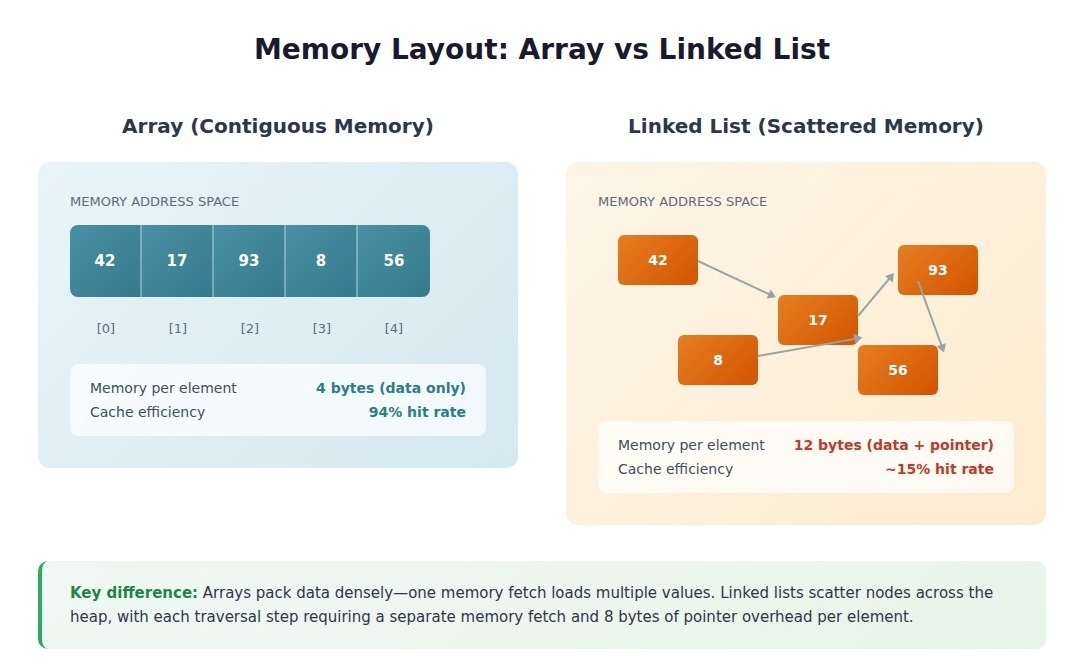

- Contiguous means the CPU can load neighboring elements speculatively

- Index access means no pointer chasing, no cache misses from scattered memory

Array time complexity:

Array types: the trade-offs nobody explains

The textbook taxonomy of arrays feels academic until you hit a production bug because you picked the wrong type.

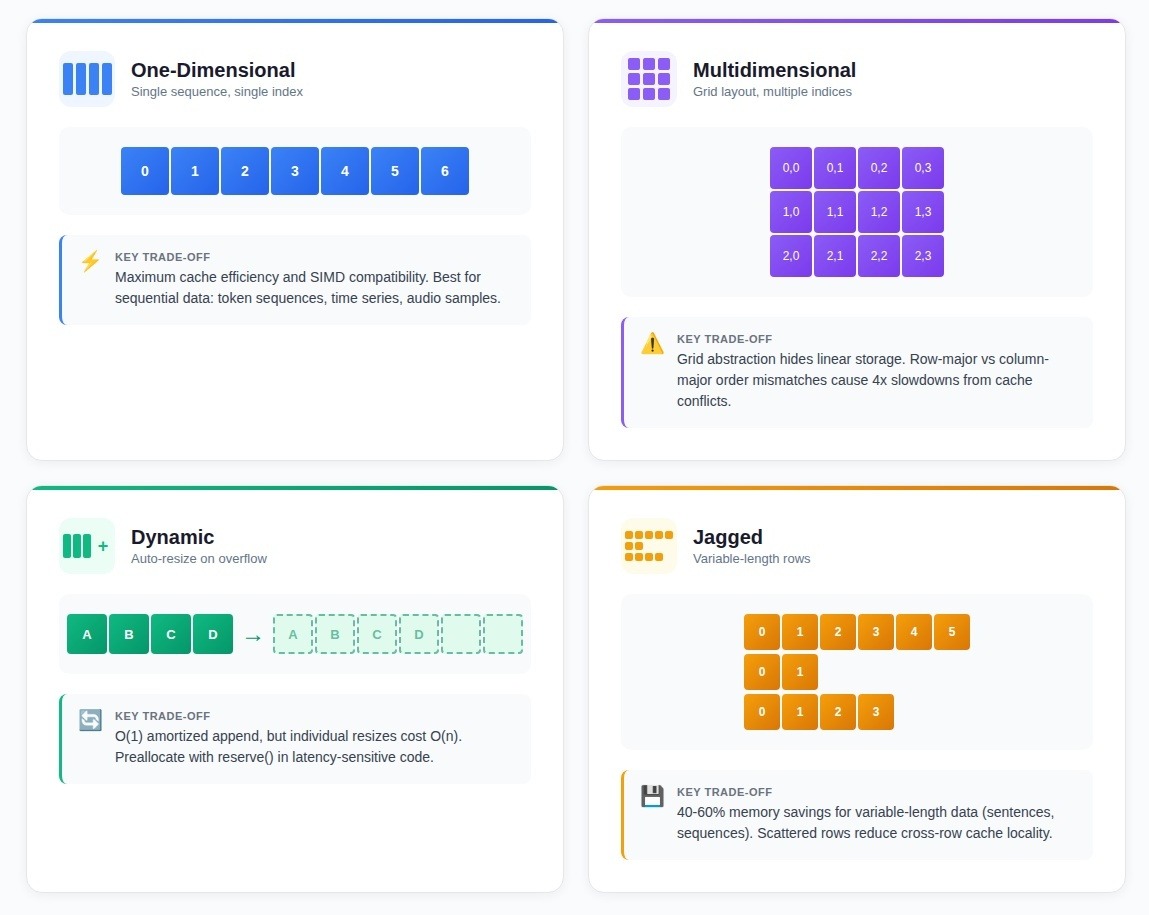

One-dimensional arrays

A single sequence of elements, accessible by one index. Declaring float weights[1000] allocates 4,000 contiguous bytes with O(1) access.

Most production arrays are one-dimensional: token sequences in language models, time series data, audio samples. The simplicity enables cache efficiency and vectorization that more complex structures sacrifice.

Multidimensional arrays

Elements arranged in rows and columns, accessible by multiple indices. Image pixels, game boards, matrices.

The critical detail: despite the grid abstraction, multidimensional arrays are stored linearly. Row-major order (C, Python) stores row 0, then row 1. Column-major order (Fortran, MATLAB) stores columns first.

Teams mixing libraries with different layouts see 4x slowdowns from cache conflicts—the "bug" is invisible in the code because both approaches are "correct."

Dynamic arrays

Arrays that resize automatically when capacity is exceeded. C++ vector, Java ArrayList, Python list.

When full, a dynamic array allocates 1.5-2x more memory, copies all elements, then frees the old allocation. Appends average O(1) amortized, but individual resizes cost O(n). Latency-sensitive systems preallocate with vector::reserve() to eliminate resize surprises.

Jagged arrays

An array of arrays where each inner array has different length. Unlike rectangular arrays, jagged arrays allocate only what each row needs.

The trade-off: rows are separate allocations scattered in memory, reducing cache locality. For NLP preprocessing where sentence lengths vary from 3 to 300 tokens, jagged arrays save 40-60% memory over rectangular allocations with no measurable throughput impact — because row-independent processing doesn't need cross-row cache locality anyway.

Why contiguous memory matters: the performance gap nobody teaches

Code that looks identical at the algorithmic level shows 3-5x performance differences purely from memory layout. The gap compounds under load in ways that reshape what's actually feasible.

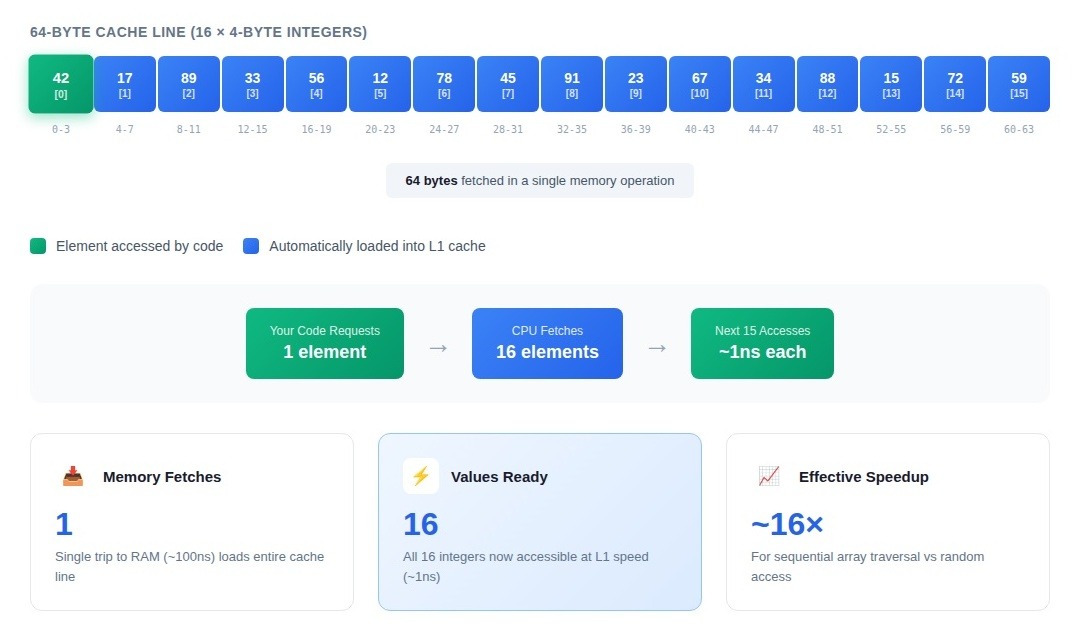

Cache lines: 64 bytes at a time

Modern CPUs don't fetch memory one byte at a time. They pull entire cache lines—64 bytes on x86 architectures. Access one array element, and the processor loads the surrounding elements into L1 cache, betting you'll need them next.

That bet pays off spectacularly with arrays. Processing 4-byte integers means a single cache line holds 16 consecutive values. Touch the first element, and the next 15 accesses hit L1 cache at sub-nanosecond latency instead of the 100+ nanosecond round-trip to main memory.

A linked list we profiled took 8.2 seconds to process 10 million records. The equivalent dense array: 1.4 seconds. Same algorithm, same data volume. The linked list scattered nodes across the heap; each traversal step missed the cache and fetched from main memory. The array version hit L1 cache 94% of the time after the initial load.

Hardware prefetching

CPU prefetchers watch memory access patterns and speculatively load data before you request it. Sequential array access creates the simplest possible pattern: address + 64, address + 128, address + 192. The prefetcher locks on immediately.

By the time your loop reaches element 100, the prefetcher has already pulled elements 120-135 into cache. Tree traversals and hash table lookups can't benefit—the next memory address depends on data values, not predictable offsets. The prefetcher sits idle.

Memory bandwidth utilization

Modern CPUs transfer 50-100 GB/s from DRAM to processor. Arrays maximize that bandwidth by packing data densely — every transferred byte contains useful information.

Linked lists include a pointer (8 bytes on 64-bit systems) with each node. Storing 4-byte integers means 67% of memory traffic is pointer overhead. You've cut effective bandwidth by two-thirds before touching any data.

SIMD and vectorization: why arrays unlock hardware parallelism

Modern CPUs contain execution units designed to process multiple array elements simultaneously. These units sit idle when fed pointer-chased data structures.

Single instruction, multiple data (SIMD)

One CPU instruction processing 4, 8, or 16 values at once. An AVX2 instruction adds eight 32-bit integers in a single cycle—but only if those integers sit consecutively in memory.

Processing a million floats with vectorized code: 12ms. The same operation using pointer-chased access: 89ms. The CPU can't predict where the next element lives, so it processes one value at a time while seven SIMD lanes remain idle.

Compiler auto-vectorization

Compilers can vectorize loops automatically, but they need guarantees: memory accesses won't overlap, stride patterns are predictable. Arrays provide both naturally.

A team processed bounding box coordinates stored as a vector of structs. The compiler generated scalar instructions—it couldn't prove struct padding wouldn't cause alignment issues. Restructuring to four separate arrays (all x coordinates, all y coordinates, all widths, all heights) let the compiler emit AVX instructions automatically. Same algorithm, 4.2x faster.

Branch prediction

Arrays create predictable control flow. Iterating through elements of the same type means conditional branches show consistent patterns. A tokenization pipeline achieved 97% branch prediction accuracy because the loop structure was identical for every element.

Polymorphic object processing forces different code paths per element. A data validation system with polymorphic objects spent 23% of execution time on branch mispredictions. Restructuring to separate arrays per type dropped misprediction overhead to 3%.

The advantages stack multiplicatively: contiguous memory enables prefetch, predictable access enables SIMD, homogeneous types enable branch prediction. A well-structured array pipeline runs 8-12x faster than equivalent code using scattered allocations—not because any single optimization is dramatic, but because friction disappears at every level.

When arrays win (and when they don't)

Arrays dominate when:

- Sequential processing: Token sequences, image pixels row-by-row, time series windows. Access pattern is "next, next, next"—exactly what modern CPUs accelerate.

- Known or estimable size: Training batch construction is ideal. You know exactly how many examples fit, allocate once, process without reallocation.

- Read-heavy workloads: Batch inference, data transformation pipelines, anything where you build once and iterate many times.

Arrays fail when:

- Frequent mid-array insertions: Inserting at position 100 in a 10,000-element array moves 9,900 elements. A team used a sorted array for "cache efficiency" in a priority queue. Each insertion touched an average of 4,200 elements. Switching to a heap dropped insertion time by 94%.

- Sparse data: Feature vectors with 100,000 possible positions but 50 used per example. Arrays allocate space for all 100,000. Sparse representations reduce memory 85% while maintaining throughput.

- Unpredictable growth: Constant resizing kills performance. A document processing pipeline spent 60% of execution time on memory allocation as arrays grew. The fix: preallocate to the 75th percentile of expected size.

- Frequent membership tests: Hash sets dominate. User ID validation measured 2.1ms per batch with array checking versus 0.14ms with a hash set.

Production patterns: what breaks under load

The bugs that take down production systems don't come from misunderstanding what arrays are. They emerge from missing operational details that only matter at scale.

Boundary validation trade-offs

A high-throughput pipeline checked bounds on every array access. Under load (50,000 samples per second), those checks consumed 18% of CPU cycles. The team removed them, then spent three weeks debugging intermittent memory corruption.

The production pattern: validate at system boundaries where external data enters. Compile with assertions in development, strip in release. Internal bound violations represent logic errors—if you're checking every access, you've already lost.

Memory alignment for SIMD

A training pipeline showed bizarre performance variance: identical batch sizes taking anywhere from 240ms to 890ms. SIMD instructions fell back to scalar execution when memory alignment was wrong—and malloc() doesn't guarantee SIMD alignment. Whether a batch got properly aligned was effectively random.

Capacity planning

A document processing pipeline spent 60% of execution time on memory allocation. Arrays started at capacity 10, doubling when full—triggering 8-12 reallocations per document.

The fix: preallocate based on measured data distribution. Set initial capacity to the 75th percentile. Accept some memory waste to eliminate most reallocations.

Zero-copy architecture

A pipeline where seven transformation stages each allocated a new array. At 1,000 batches per second: 350 million allocations per hour.

The zero-copy principle: in high-throughput array processing, every unnecessary copy or allocation represents sacrificed performance. Rebuilding with explicit buffer management—a pool of reusable buffers passed by pointer through in-place transformations—dropped allocation rate from 350 million per hour to 800 per second. Throughput increased 34%.

The trade-off: zero-copy architectures sacrifice safety for performance. Five pipeline stages holding pointers into the same buffer creates aliasing that makes correctness harder to verify. This tension between abstraction and performance defines production work at scale.

Why this matters for AI systems

These aren't academic optimizations. Systems training frontier models process billions of array operations per forward pass. Weight matrices are arrays. Attention scores are arrays. Embedding lookups are array indexing.

When a training run completes in three weeks instead of three months, it's often because someone understood that memory layout determines whether hardware accelerates your code or fights it.

The same systems thinking shapes quality in human processes. Recognizing when "theoretically correct" loses to "practically fast." When elegant abstractions cost too much. When the textbook answer isn't the production answer.

Apply technical expertise to AI development

Understanding why arrays outperform alternatives at the hardware level requires the same systems thinking that shapes quality AI training data: recognizing constraints, evaluating trade-offs, and knowing when optimization creates problems elsewhere.

Frontier AI development needs contributors who understand what "good enough" means in context — who can evaluate complex outputs beyond surface metrics and recognize when synthetic data captures real-world complexity versus when it doesn't.

If your background includes technical depth, domain expertise, or the critical thinking to evaluate nuanced trade-offs, DataAnnotation positions that expertise at the frontier of AGI development.

To join over 100,000 contributors building this infrastructure:

- Apply at DataAnnotation

- Complete the Starter Assessment (one attempt — read instructions carefully)

- Receive approval (typically within days)

- Select projects matching your expertise and start contributing

No fees. Flexible hours. Compensation reflects the technical depth required.

.jpeg)