A message queue processed 4 million jobs without incident. Then it brought an entire notification system to a halt because a single email-rendering service slowed from 200 milliseconds to 12 seconds.

The on-call engineer had twelve years of distributed systems experience. She still spent three hours tracing the cascade before finding the root cause.

The queue worked perfectly: FIFO order maintained, no messages lost. But theory doesn't account for what happens when one slow consumer creates a backlog that cascades into memory pressure, then connection timeouts, and finally a 3 AM page.

This guide covers how queues actually behave in production, the performance characteristics that matter, and the failure modes that surface at scale.

What is a queue?

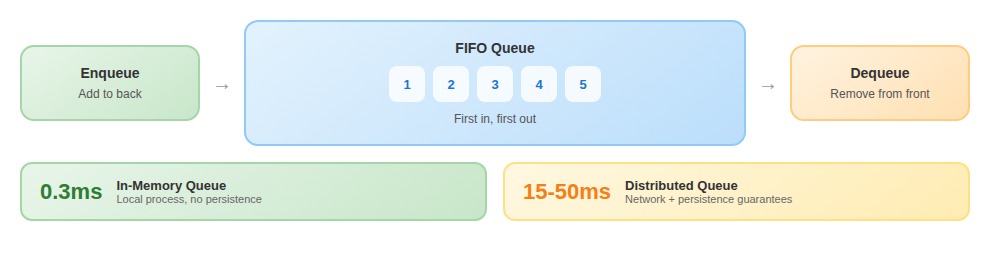

A queue is a data structure that stores elements in First-In-First-Out (FIFO) order. The first element added (enqueued) is the first element removed (dequeued). This maps directly to how work moves through real systems.

In AI training pipelines, annotation tasks move through multiple processing stages: a batch of 10,000 images enters the labeling queue, annotators process them in order, validated labels move to the next queue, then training jobs consume them sequentially. Break FIFO ordering anywhere in that chain, and you introduce subtle data dependencies that become debugging nightmares.

Every queue supports two primary operations: enqueue (add to back) and dequeue (remove from front). The theory is simple. The reality is a 50x performance gap: enqueue operations run at 0.3 milliseconds for in-memory queues and 15-50 milliseconds for distributed queues with persistence guarantees. At 100,000 tasks per hour, that difference determines whether your system hums or crawls.

Dequeue is where operational complexity surfaces. The operation might block if the queue is empty, return immediately with a null value, or wait with a timeout. Mixing these modes across different consumers can leave some workers idle while others are overwhelmed.

When FIFO guarantees break

First-In-First-Out sounds straightforward: messages arrive in order, leave in order. This guarantee holds perfectly in single-threaded, in-memory implementations. Put three items in a Python queue.Queue, and you'll get them back in exactly that order.

from queue import Queue

q = Queue()

q.put("first")

q.put("second")

q.put("third")

print(q.get()) # first

print(q.get()) # second

print(q.get()) # thirdThe problems start when systems scale. Teams discover their "FIFO queue" reorders messages because they run multiple consumer threads without proper coordination. Message queues deliver in order per consumer. Spin up five consumers, and suddenly messages 1 and 6 process simultaneously, completing in whatever order workers finish.

This breaks in three specific ways: network partitions isolate nodes and cause messages to complete out of sequence when connectivity restores; priority handling causes high-priority messages to jump ahead while downstream logic still expects FIFO semantics; and redelivery after failure means a crashed consumer's message gets redelivered after subsequent messages have already processed.

True FIFO requires single-consumer processing or extremely careful coordination. Most production systems accept "mostly FIFO" and design around the exceptions.

Memory management and bounded vs. unbounded queues

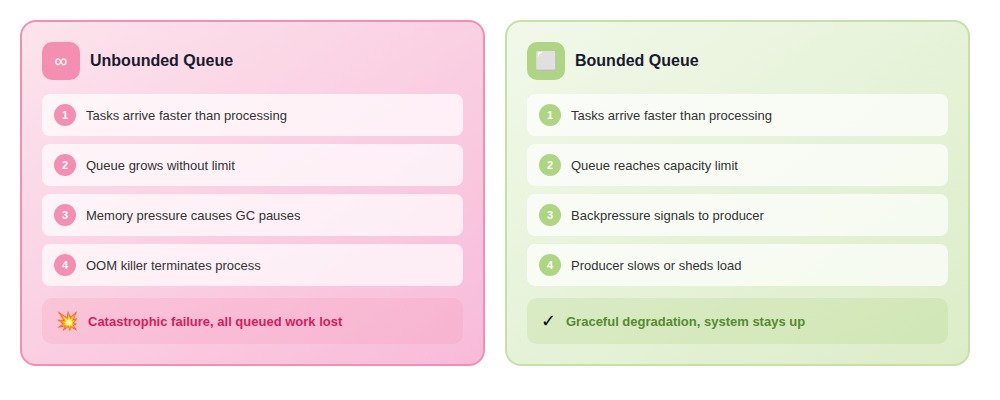

This is where operational and design decisions collide. An unbounded queue seems safe: you never reject work, just buffer it until you can process it.

I watched this choice bring down entire systems.

I debugged a training pipeline where annotation tasks queued faster than workers could process them. The queue grew to 40GB over six hours, then the process OOMed and crashed. All the queued work was lost. The team restarted with a bounded queue, and suddenly, they had to design actual backpressure handling.

The failure mode is insidious because it's gradual. Memory usage creeps up. Everything seems fine. Then you hit the kernel's memory limit, and the process dies instantly. No graceful degradation, no warning. Teams then add memory monitoring alerts, but by the time an alert fires, they often have only seconds from OOM.

Bounded queues force you to decide: what happens when the queue is full?

Block the producer: Ensure you watch for deadlocks if producers hold locks while enqueueing.

Drop the message: But monitor for silent data loss.

Return an error: Proper separation of concerns, but complexity moves to producers.

In our deployments, bounded queues with blocking work best when you control the entire pipeline. For external APIs, you need error returns. You can't block a client for 30 seconds waiting for queue space.

The industry defaulted to unbounded queues because they're easier to reason about. "Just buffer it" feels safer than "reject it." But safety that fails catastrophically isn't safety. It's deferred failure with compound interest.

Production failure modes

Thundering herd: Fifty consumers on a single queue, messages arriving faster than any individual can process. One team processed 120 tasks per second with ten workers. They added twenty more expecting linear scaling—throughput dropped to 95 tasks per second.

The problem is contention at the dequeue point. The fix came from an engineer with HFT experience: shard into partitioned queues. Instead of thirty workers fighting over one dequeue point, six groups of five workers each pulled from dedicated partitions. Throughput jumped to 340 tasks per second. Same worker count, 80% less contention.

Memory exhaustion: In-memory queues fail catastrophically when they run out of space. A queue consumed 47GB before the kernel OOM killer terminated the process and took down adjacent services. Worse: memory pressure causes garbage collection pauses, which slow consumers, which causes more queue buildup.

The fix: a circuit breaker that sheds load at 70% memory capacity rather than waiting for alerts at 90%.

Poison messages: A single malformed message can brick an entire queue if error handling isn't bulletproof. One JSON payload contained a Unicode character that crashed the deserialization library. The message sat at the front; consumers would pull it, crash, restart, pull again, crash again. 15,000 valid messages sat behind this single poison pill.

def process_with_retry(queue, max_retries=3):

retry_counts = {}

while True:

msg = queue.get()

msg_id = msg.get("id")

if retry_counts.get(msg_id, 0) >= max_retries:

dead_letter_queue.put(msg) # Move to DLQ

continue

try:

process(msg)

except Exception:

retry_counts[msg_id] = retry_counts.get(msg_id, 0) + 1

queue.put(msg) # Requeue for retryRace conditions in distributed consumers: Two consumers pull what they think are different messages, but visibility timeout semantics mean both process the same one. A task meant to be idempotent—"assign this data batch to an annotator"—incremented a counter. The counter ended up wrong, downstream billing was wrong, and the error wasn't detected for six days.

If processing takes longer than the visibility timeout, the message becomes visible again. Clock skew makes this worse—up to 3 seconds of drift between instances in the same availability zone means time-based visibility timeouts behave inconsistently.

Head-of-line blocking: A single slow or stuck item at the front blocks all items behind it. A training data ingestion pipeline ground to a halt because one corrupted annotation file triggered a 60-second timeout. While that timeout ran, 15,000 valid files queued behind it. The queue was healthy—depth grew, no errors logged—but throughput dropped to zero.

The fix: timeout-and-park. If processing exceeds 10 seconds, move the item to a quarantine queue and continue. The quarantine queue gets human review. Throughput stabilized, and the team discovered 0.3% of their annotation files had structural issues worth fixing upstream.

Priority queues and their trade-offs

FIFO works until you encounter the reality that not all work carries equal weight. A user's password reset shouldn't sit behind 10,000 analytics jobs nobody would notice running an hour later.

A priority queue breaks FIFO: items exit by priority value, not arrival order. The performance tax is immediate. Standard FIFO runs enqueue and dequeue in O(1). Adding priority turns dequeue into O(log n) with a binary heap. One team migrated to a priority implementation and saw peak throughput drop 40%.

The higher cost shows up in operational complexity. With FIFO, debugging is straightforward—trace through in arrival order. Priority queues fracture that narrative. Priority schemes also become a crutch for poor system design. One team had 127 distinct priority levels because different product managers kept arguing their feature was more critical.

Priority inversion is the failure mode unique to priority systems. A low-priority task acquires a lock on a shared resource, then gets preempted by medium-priority work. When a high-priority task arrives needing that same resource, it can't proceed—blocked by the low-priority task, which can't finish because medium-priority work preempts it. Your high-priority task now waits behind medium-priority work.

This exact pattern appeared in a model production system. Priority levels for annotation tasks: urgent customer deliveries at priority 1, standard work at priority 5, batch reprocessing at priority 10. Batch jobs acquired database connections, then got preempted by standard work. When urgent jobs arrived, they couldn't get connections. The priority queue worked perfectly, but resource contention made it irrelevant.

Why queue architecture matters for frontier AI

These aren't abstract infrastructure problems.

The systems training frontier models coordinate millions of annotation tasks across global contributor pools. A poison message means thousands of expert evaluations sit unprocessed while the same error loops. A priority inversion means urgent quality corrections (the kind that catch a model learning the wrong pattern) wait behind routine batch work. Head-of-line blocking means one malformed task holds up an entire training run.

The humans debugging these systems need production intuition: the ability to trace symptoms back to root causes that queue metrics alone won't reveal. And the humans working within these systems, the contributors who evaluate model outputs, catch edge cases, and maintain quality at scale, need infrastructure that doesn't silently drop their work or reorder it in ways that corrupt the training signal.

Queue architecture determines whether human expertise reaches the model intact.

Contribute to AGI development at DataAnnotation

The queue implementations powering frontier AI systems face the same challenges at unprecedented scale. They coordinate millions of tasks across distributed workers, maintain consistency without sacrificing throughput, and ensure quality doesn't degrade as volume increases.

These aren't just infrastructure problems. They're systems that require human judgment to evaluate complex outputs, handle edge cases, and maintain standards that no automated check can enforce.

Building that infrastructure means understanding both the technical architecture and the expertise required to operate within it. The competitive advantage in AI training isn't processing more tasks. It's processing the right tasks with contributors who recognize quality when they see it.

If your background includes the kind of systems thinking that traces failures back to root causes, that's what AI training infrastructure needs.

Over 100,000 remote workers have contributed to this infrastructure.

If you want in, getting from interested to earning takes five straightforward steps:

- Visit the DataAnnotation application page and click "Apply"

- Fill out the brief form with your background and availability

- Complete the Starter Assessment, which tests your critical thinking skills

- Check your inbox for the approval decision (typically within a few days)

- Log in to your dashboard, choose your first project, and start earning

No signup fees. We stay selective to maintain quality standards. You can only take the Starter Assessment once, so read the instructions carefully and review before submitting.

A queue that works in theory and fails in production isn't broken. It's a reminder that systems are only as reliable as the judgment behind their design.

Apply to DataAnnotation if your expertise includes the kind of production thinking that sees and fixes failure modes before they surface.

.jpeg)