Every company hiring software engineers claims they want top talent. They post job descriptions listing the same frameworks, the same languages, the same generic requirements. Then they filter candidates using signals that have almost nothing to do with job performance and wonder why most hires underperform or leave within months. The disconnect isn't accidental. It's structural.

The disconnect is fundamental because companies misunderstand what actually makes engineering work. They optimize job descriptions for keyword matching and applicant volume, then filter using signals that have almost nothing to do with on-the-job performance.

The software engineering job market is broken because both sides optimize for the wrong signals, measure the wrong things, and make decisions based on proxies that have lost touch with what actually matters in production environments.

What do software engineer jobs require?

Engineers apply for positions that list React, TypeScript, AWS, Docker, Kubernetes, and GraphQL in the requirements. The actual work turns out to be reading legacy PHP code, debugging third-party API integrations, and attending standups about why the deployment pipeline broke again. The job posting described a modern engineering role. The actual job is keeping a 2015 codebase alive.

This information asymmetry runs in both directions. Companies know what their day-to-day reality looks like, but can't say "we need someone to maintain our aging monolith" because that won't attract candidates. Engineers see the requirements list and either feel underqualified or assume it's accurate. It usually isn't.

Stack requirements vs. actual work

When teams compare what they're actually building versus what their job postings list, the disconnect is stark. A company will post requirements for Next.js, TypeScript, Tailwind, PostgreSQL, Redis, and AWS. The hired engineer spends their first six months in a Django monolith with jQuery sprinkled throughout, because that's what actually runs in production.

Companies list their aspirational stack (what they want to migrate to) rather than their operational stack (what they need maintained). The senior engineer who gets hired to "build modern React applications" ends up writing Python scripts to patch data inconsistencies in a MySQL database, because that's the urgent work that's been piling up.

A role that lists "experience with microservices" might mean any of the following:

- Actually architecting microservices from scratch (rare)

- Maintaining existing microservices built by someone else (common)

- Working in a monolith the company wants to eventually break apart (very common)

- Working in what someone called "microservices" but is actually three large services with tight coupling (extremely common)

The actual requirement isn't mastery of Kubernetes orchestration. It's the ability to read unfamiliar code quickly, understand system dependencies, and fix issues without comprehensive documentation.

The communication shift

What's genuinely changed in the past two years isn't the technical work, rather how much time engineers spend coordinating instead of coding. We've seen this pattern across thousands of technical contributors: the engineers who struggle aren't usually weak technically. They're uncomfortable with the amount of communication the job now requires, and nobody told them the role had changed.

Senior engineers now divide their time among meetings, code reviews, documentation, and async communication. The actual heads-down coding happens in compressed windows between standups, planning sessions, and architecture discussions.

As teams were distributed post-pandemic and AI tools accelerated individual coding speed, the bottleneck moved from "writing the code" to "making sure everyone's writing code that works together." The engineer who can knock out a feature in three hours but doesn't document their approach or communicate with dependent teams creates more friction than the engineer who takes six hours but keeps everyone aligned.

Job postings rarely capture this reality. They list technical requirements but don't mention that the role involves writing design docs for non-technical stakeholders, reviewing 10–15 pull requests per day from distributed team members, and debugging issues by coordinating across multiple teams in different time zones.

The engineers who struggle most aren't usually weak technically. They're uncomfortable with the amount of communication the job requires.

AI tooling as baseline expectation

The communication shift compounds with another change: AI assistance is now table stakes.

Six months ago, using Copilot or ChatGPT for coding was a productivity edge. Today, it's assumed. Companies expect engineers to move faster on routine implementation work. A task that used to be estimated at two days is now expected to take four to six hours, because the assumption is you're using AI tools to handle the mechanical parts.

Experience inflation

Experience requirements in job postings have completely decoupled from reality. '5+ years experience' appears on roles that require 18 months of solid fundamentals. The numbers exist because HR needs defensible criteria and hiring managers want to filter volume, not because anyone actually needs five years to do the work.

What companies need is rarely more years of experience. It's specific, demonstrable competencies: Can you read unfamiliar code and identify the bug within an hour? Can you take a vague product requirement and ask the right clarifying questions? Can you estimate work accurately enough that dependencies don't slip?

Why does software engineer hiring feel broken?

If companies struggle to find qualified engineers while filtering out capable candidates, the problem isn't the talent pool. It's how they evaluate it.

The assessment gap

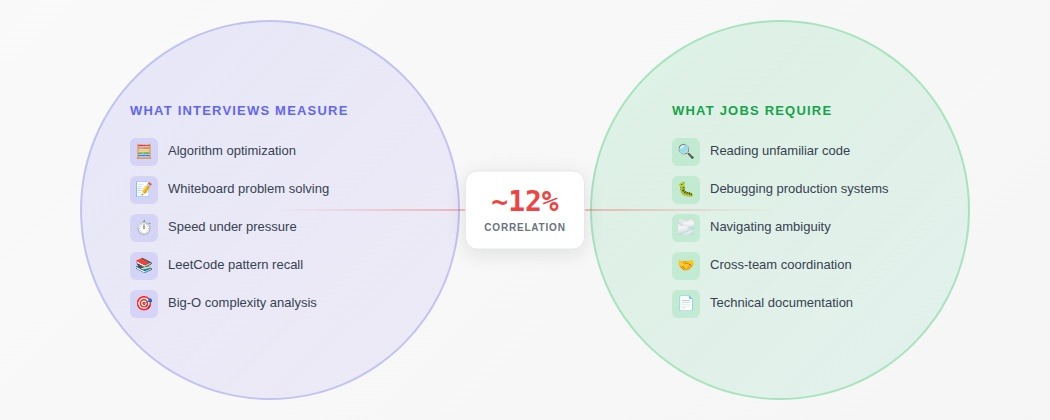

Companies know their engineers spend most of their time reading unfamiliar code, coordinating across teams, and debugging production systems. Then they evaluate candidates by asking them to invert binary trees on a whiteboard.

Engineers ace algorithm interviews by optimizing dynamic programming solutions. Then they struggle when faced with debugging a distributed system or negotiating technical tradeoffs with product managers.

Companies routinely find algorithm assessment scores have almost no correlation with job performance. What actually predicts success? Previous experience with similar technical complexity and demonstrated ability to work through ambiguous requirements. Most interview processes test neither.

Why the process stays broken

The disconnect persists because fixing it is expensive. Evaluating whether someone can debug a complex system, communicate technical tradeoffs, or navigate ambiguous requirements takes hours of skilled interviewer time. Algorithm puzzles take 45 minutes and have clear right/wrong answers.

Companies optimize for interviewer convenience and legal defensibility, not predictive accuracy. A standardized algorithm screen is easy to defend if a hiring decision gets challenged. "We asked everyone the same questions and scored them on the same rubric." That the rubric measures nothing relevant to the job is a secondary concern.

The result: an adversarial system where candidates optimize for passing tests that don't measure job performance, and companies complain they can't find qualified engineers while filtering out capable people who didn't grind LeetCode for three months. Both sides know the game is broken. Neither side has enough leverage to change it unilaterally.

The specialization trap

Body shop dynamics create a specific career trap: the more specialized you become, the less leverage you actually have.

Companies post job listings for "Senior ML Engineer with 5+ years PyTorch experience" or "Staff Backend Engineer specializing in distributed systems." But when it comes time to negotiate compensation, they treat these roles as interchangeable units. They want the depth of expertise, but structure compensation as if all senior engineers are fungible resources.

When a company posts a specialist role, they're signaling a technical need: someone who understands how to optimize inference latency for large language models or architect distributed consensus systems. But the budget approval process doesn't account for specialization. It accounts for level. A Senior Engineer budget is a Senior Engineer budget, regardless of whether the role requires commodity web development skills or deep expertise in a narrow technical domain.

A Staff Engineer who's spent three years building expertise in Kubernetes operators is incredibly valuable to their current employer. But if that role ends through layoffs or political dynamics, they're competing for a much smaller pool of opportunities. Each level requires greater specialization, but that specialization reduces your market liquidity.

General engineering skills degrade slowly. Specialized knowledge ages in internet time. Engineers who specialized in TensorFlow 1.x optimization found their entire body of knowledge became historical context when TensorFlow 2.x shifted everything to eager execution.

Where to find software engineer jobs

Job listings function primarily as legal documentation, not communication. The posting says "5+ years experience with distributed systems" because HR needs that language. What actually gets you the interview is that your former colleague now leads the infrastructure team and mentioned your name.

Major job boards

LinkedIn, Indeed, and Glassdoor optimize for employer convenience rather than match quality. A posting can generate 500+ applications in 48 hours. Companies respond by implementing keyword filters that eliminate most of these before they are reviewed by a human.

Most positions on major boards have already been filled internally or through referrals by the time they're posted. Their actual value is market intelligence: which companies are expanding, what the current market rate language looks like, and which technologies are trending.

Referrals

A referral from a current employee changes your application from 1 in 500 to 1 in 5. Some companies build cultures where 40–50% of hires came through referrals.

If you don't have an existing network, the tactical approach is building specific connections rather than collecting LinkedIn contacts. Contribute to open source projects maintained by companies you want to join. Write detailed technical posts about problems you've solved. A referral from someone who's read your analysis and thinks you're sharp carries more weight than a referral from someone who met you once at a networking event.

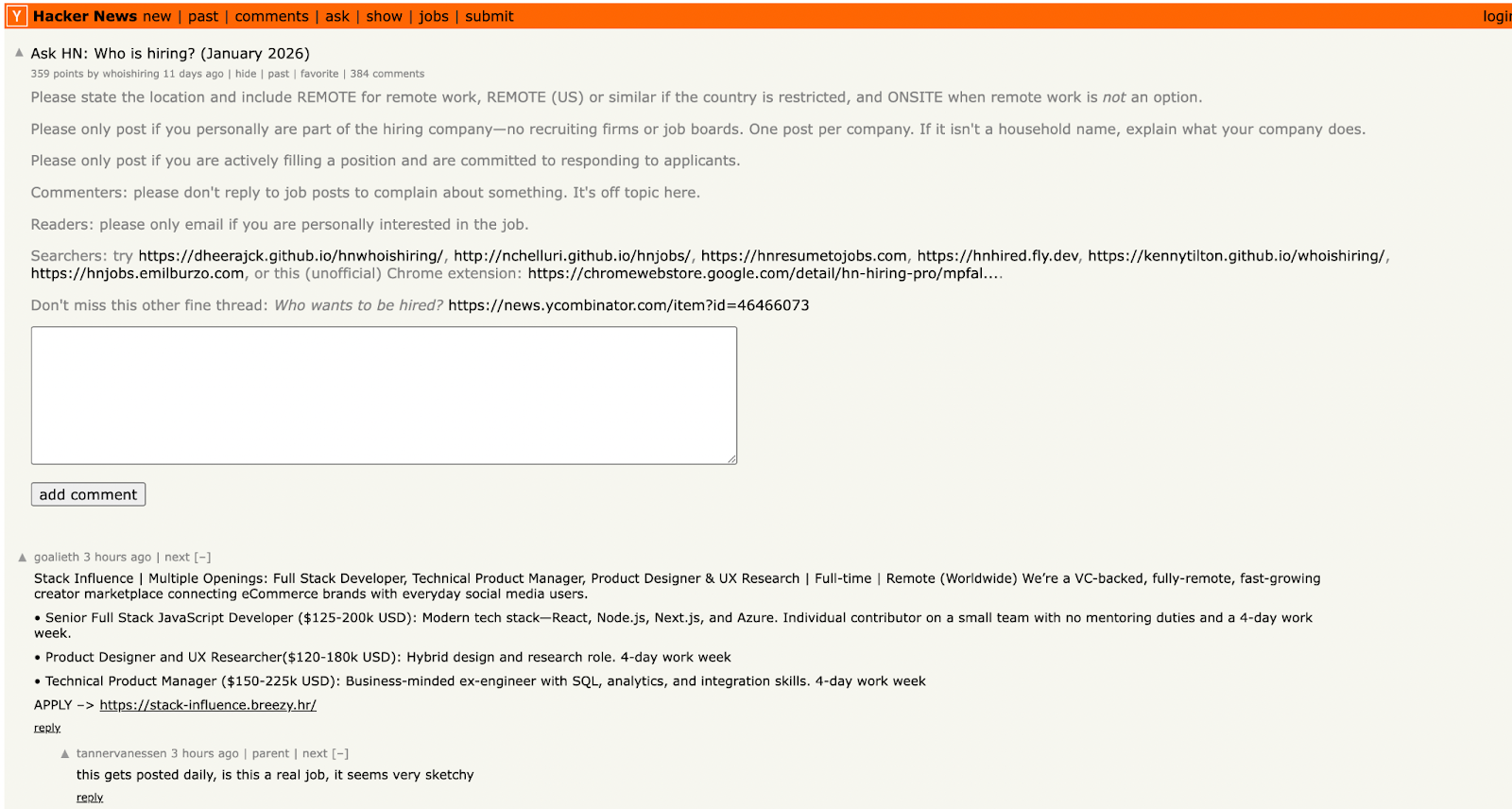

Hidden channels

Technical community boards like HackerNews hiring threads, community Slack and Discord channels, and niche subreddits self-select for people actively engaged in technical communities. The applicant pools are smaller, and the signal is higher.

Remote software engineer jobs

Remote work has become standard for most engineering roles, but the coordination overhead has increased proportionally. The engineers who thrive remotely aren't just technically competent; they're effective asynchronous communicators who can document decisions, write clear tickets, and maintain visibility without physical presence.

Alternative hiring models

This is where DataAnnotation fits. Traditional hiring optimizes for credentialing and interview performance. Alternative models optimize for actual ability to do the work. If you can train AI systems effectively, that matters more than whether you can invert a binary tree on a whiteboard.

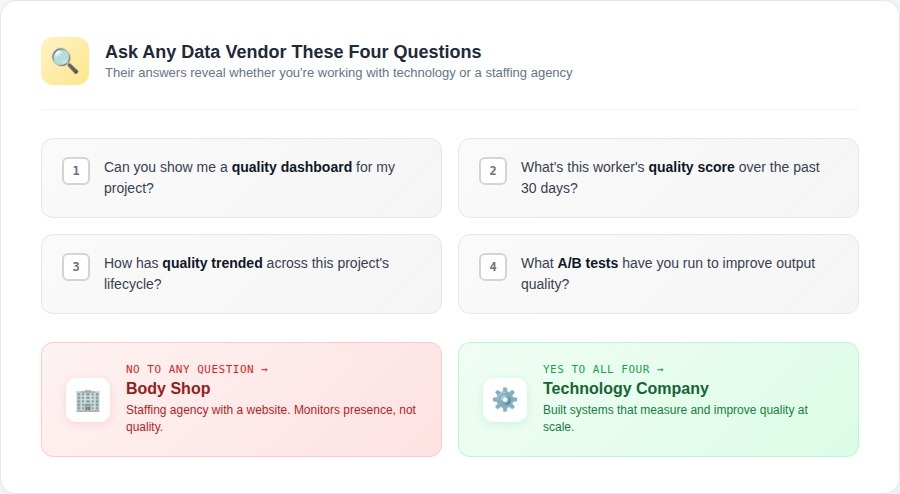

The distinction matters: most platforms in this space are body shops masquerading as technology companies. They recruit people, glance at resumes, and pass warm bodies to clients. They have no systems to measure whether the work is actually good, so they monitor presence instead of quality. Can they show you a worker's quality score? Quality trends over time? A/B tests on process improvements? They can't, because they never built the technology.

DataAnnotation operates differently. We gather thousands of signals about every contributor, including response patterns, code execution results, model-based quality assessments, and review accuracy. Our algorithms identify the top performers in any domain and detect the people trying to game the system. When you're good, the data shows it. When you're not, no credential saves you.

Looking for work that evaluates your actual engineering judgment? DataAnnotation pays $40+ per hour for coding projects where your ability to evaluate code quality matters more than your ability to solve whiteboard puzzles.

What actually drives career growth

Engineers go through the same exhausting cycle every few months: update their resumes, grind on algorithm prep, navigate interviews, negotiate offers, start over. The tactics work. They get the next job. But the process never gets easier. Five years in, they're still spending the same energy on the same activities, just with slightly higher compensation.

The engineers whose searches get progressively easier are doing something fundamentally different. They're building capabilities that compound across jobs, making each transition simpler than the last.

AI engineers at frontier labs who move most easily between opportunities share specific patterns. They've built in public through open source contributions, technical writing, and conference talks, so their capabilities are visible independent of their employment history. They've developed expertise in specific problem domains that transcend individual tech stacks. They've cultivated the ability to explain technical decisions, document complex systems, and translate between technical and non-technical contexts.

The tactical job search skills don't compound. You perform them, get the benefit, and start fresh next time. But deep technical writing ability, domain expertise, and evaluative judgment make every subsequent search shorter because opportunities start coming to you through different channels entirely.

Building leverage that survives role transitions

Your leverage shouldn't be trapped in your employer's infrastructure. A talented engineer might spend three years building sophisticated internal tooling at a major tech company. When they leave, they have war stories but no portfolio. Their next search is harder because their expertise exists only in systems that no one outside can evaluate.

For example, AI engineers building proprietary systems often can't share implementation details. Writing extensively about evaluation frameworks, methodology, or technical approaches creates portable proof of expertise. Companies reach out based on those posts alone

Creating career optionality

The most strategically positioned engineers have built something subtle: their career isn't dependent on continuous employment. They've created capabilities and connections that generate opportunities through multiple channels.

This pattern shows up in AI training programs. Engineers join initially for supplemental income or intellectual interest. The ones who engage deeply start receiving different opportunities: consulting on evaluation methodology, advising startups on model deployment, getting pulled into technical advisory roles.

Contribute to AGI development at DataAnnotation

The same pattern that breaks engineering hiring shows up everywhere in AI development: optimizing for easy-to-measure proxies instead of hard-to-measure quality.

Companies climb leaderboards by gaming benchmarks. They hire PhDs because credentials are measurable, even though half of them can't actually do the work. The organizations that actually advance frontier AI build systems that identify people who understand nuance, handle ambiguity, and make judgment calls that can't be automated.

If your background includes technical expertise, domain knowledge, or the critical thinking to evaluate complex trade-offs, AI training at DataAnnotation positions you at the frontier of AGI development.

Over 100,000 professionals have contributed to this infrastructure.

Getting from interested to earning takes five straightforward steps:

- Visit the DataAnnotation application page and click "Apply"

- Fill out the brief form with your background and availability

- Complete the Starter Assessment, which tests your critical thinking skills

- Check your inbox for the approval decision (typically within a few days)

- Log in to your dashboard, choose your first project, and start earning

No signup fees. DataAnnotation stays selective to maintain quality standards. You can only take the Starter Assessment once, so read the instructions carefully and review before submitting.

Apply to DataAnnotation if you understand why quality beats volume in advancing frontier AI, and you have the expertise to contribute.

.jpeg)